Victorian Winchester – boy gangs, apprenticeships and wild soldiers

Barry Shurlock presents excerpts from a memoir submitted by a Winchester journalist working on a rival paper to the Chronicle in 1908, and discovered there 25 years ago ‘at the bottom of an old filing cabinet’.

ONE of the frustrations of exploring the past is that most of what survives was written by the ‘great and the good’. Hence, these recollections of Winchester written by an ‘ordinary person’ are of special interest – not so much for ‘hard facts’, but as a record of what people felt and valued.

Henry (‘Harry’) Moody Junior (1840-1921) lived through the Victorian age in Winchester, working on the Hampshire Observer, a newspaper published by Warren & Son. His career went from ‘printer’s pressman’ in 1871, to ‘reporter and letter-press printer’ ten years later, and in 1891’newspaper correspondent’.

Harry’s namesake father made a life in local history. He wrote several popular books, including Antiquarian and Topographical Sketches of Hampshire, published in 1846. He was curator of Winchester’s first museum for 24 years, initially in Hyde Abbey School, and then in Jewry Street.

The Observer was bought by the Chronicle in 1957 and it’s tempting to suggest that that’s the path taken by Harry’s manuscript. But on the last page he wrote: ‘I trust the readers of the Hampshire Chronicle may feel as interested in reading, as I am pleased in recalling some of the many changes our old City has passed through in the half century.’ So here it is.

IN my early days, the Winchester ‘native’ was as clannish as a Scotsman. To the advent of the railway must be attributed the decline of holding on to native rights, privileges and honour – in its place we have citizenship.

In my boyhood there was a sort of ill-feeling between Collegians, who were daily marched on to St Catherine’s Hill for exercise, and town boys. Something like ill-usage or a ducking in the river was meted out to a lone townie. But usually the Collegians were given a wide berth by running away on their approach. On the other hand, the appearance of Collegians in the town was, except with a parent, unknown.

Those living to the east of the city bridge were known as ‘Cheesehill Bobs’ and were treated as aliens. Fighting excursions were not infrequently made by the ‘Brooklands’ [boys from the Brooks] on to St Giles Hill to meet them.

Hyde parish was like an independent state of a generally peacable disposition, save toward the scholars of a new gentleman’s school opened in Hyde Street, their playground being the [Winnall] meadows.

The native in more recent years [sought] the Arbour for public playground rights. Piece by piece the open area was curtailed. Some was sold by the Corporation to the Railway Company, some to the Union authority [for the workhouse], and at the top a portion is now Clifton Road.

The whole ground was let annually for the [Feast of St Edward] in October right through the centre of the playground. Following this there was a more serious affair, the Sheep Fair, and though there was much grumbling no hostile demonstrations took place till a new road was laid out, culminating in the burning of the sheep fair hurdle stack.

The November 5th bonfire, and its attendant danger of fire-balls kicked through the streets (with often wilful damage to property) claimed as a right, was ended by the magistrates enforcing severe penalties on those brought before them.

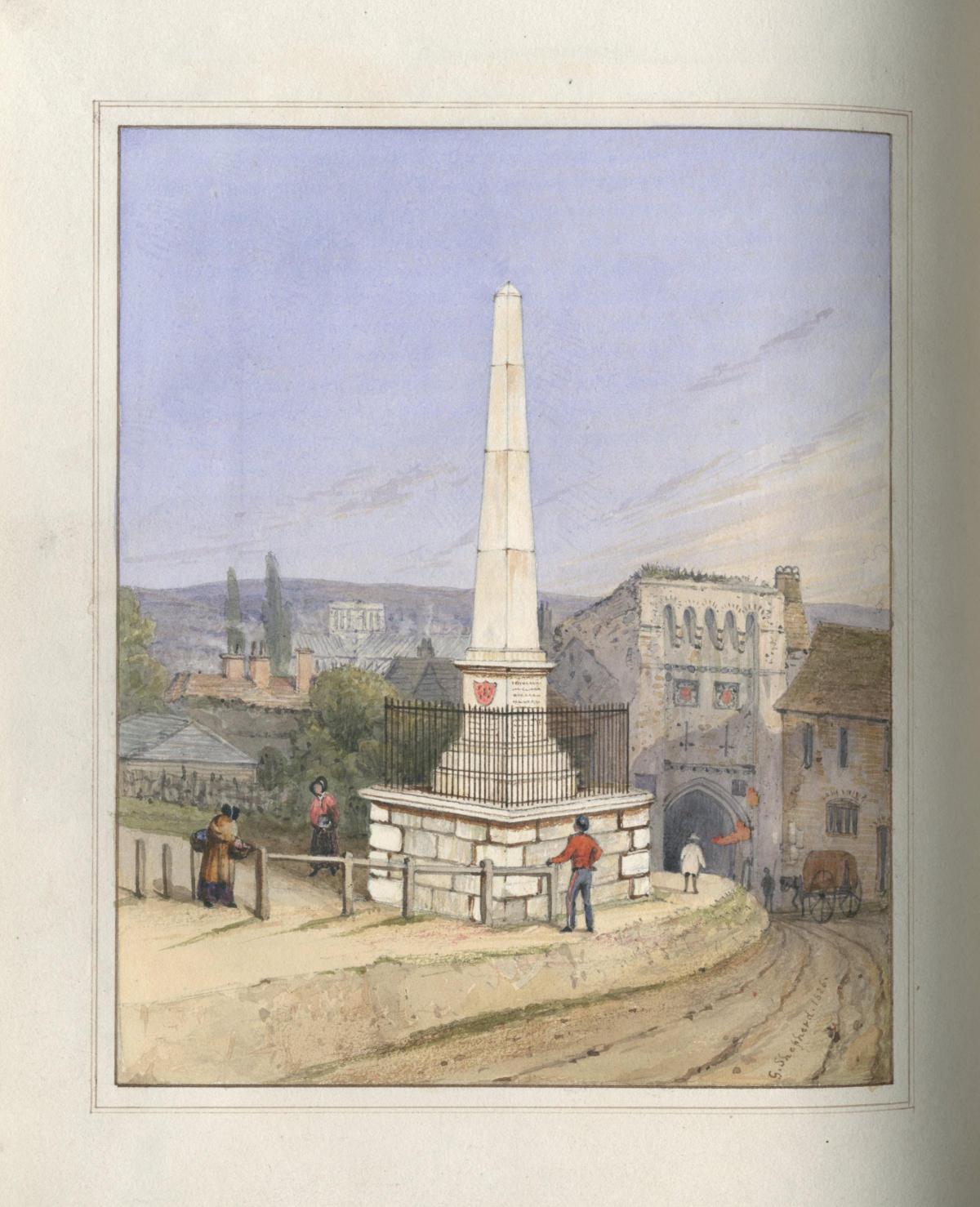

The last native or civic demonstration was the removal of the Russian gun from The Broadway to the summit of St Giles Hill. But the success of this protest and the return of the gun to its original place was in some measure due to the sympathy and help shown towards the protesters by the large gang of navvies engaged in laying sewers throughout the city.

In my younger days there existed a rivalry between the Charitable Society of Natives and that of Aliens, though their object was the same – that of apprenticing poor children, the former being native born and bred, of which they were undoubtedly proud.

Whether other charitable institutions in the city such as the Free School, Christe’s Hospital, the Cathedral and College Choristers, to which there were apprenticeships attached, were intended to be for native boys, it is an undisputed fact that the majority of apprentices were natives.

Again, there was [Sir Thomas] White’s Charity loaning free £50 to young native tradesmen to start in business. But since then, the ‘iron rail’, penny post and other things have rapidly transformed the native and alien into ‘a citizen of no mean city’, with no doubt an advantage to each and all alike, both religious and social, for there was a strong prejudice against all nonconformity, as well as the Roman Church in those days.

Womenfolk of the respectable class would not be sent out after dark unattended owing to the orgies of the military and ‘frail sisterhood’. The citizens long grumbled at this awful state of things, seemingly without power or remedy. The recruit of those days received a large bounty on enlistment – £4 or more –which he was quickly assisted in dissipating in one of the several notorious [public] houses in the town by his comrades.

The arrival home of a battalion after long foreign service was a scene in the town incredible to believe in the present day. The soldiers were virtually let run wild without discipline for three days in order to ger rid of their hard-earned savings of many years abroad.

On other occasions strong picquets [squads of military police] perambulated the streets at night and shocking cruelty was often witnessed in the ‘frog marchs’ to barracks of a drunken, violent soldier.

What a change since then, now this hideous monster of immorality is entirely stamped out and, in most cases, the licensed houses themselves. I believe the pioneer in the crusade is still amongst us in the venerable Rev. [George Augustus] Seymour [1820-1909], then living in the close.

Returning again to the young generation of that day, some of the play games are with us still, though I question if played with the same zeal. Marbles for instance, shoot ring and lob ring. These games were engaged in especially on Sundays by many past their childhood, as well as top-ring. Blood-alleys (or marbles) and Bossers (size of a tennis ball) cost a halfpenny each, whilst a box top, might cost threepence or more.

Rumpeys, the forerunner of hockey was a favourite street game. Skittles, shove-halfpenny, raffling, and quoits were amongst the pastimes of the working classes, whilst tradesmen, who had their certain [public] house for a quiet pipe (long straw provided) and ‘couver’ enjoyed a friendly game of cards or in the season engaged in bowls at the Globe, White Swan or Friary.

The mechanic of that day was in some respects more master than man. The more skilled at his trade he proved, the more liberty he took in absenting himself from his work when he chose, and this not infrequently. His bout of drinking over he returned to his work as if the natural sequence. Nor did his absence seem to give offence, if inconveniencing, his master.

Whit Monday was the great holiday festival with the masses. Benefit clubs flourished. The members assembled at their club room (public house) and, headed by a band, attended morning service at the neighbouring parish church. Then they serenaded the residences of their chief supporters and returned to the inn to feast. After the various amusements they finished the carousing with the inevitable dance on the green to the strains of loud, discordant music.

To be continued. This is an edited version of excerpts from a 34-page manuscript held by the Hampshire Record Office (3A00W/16).

CAPTIONS

All images, City of Winchester Trust

[Ed: permission without fee from Tessa Robertson, 851664]

‘Cheesehill Bobs’ beside Chesil Rectory, c1900

Middle Brook Street, c1900, haunt of the ‘Brooklands Boys’

The Russian gun that raised riots in 1908

Residents of Christe’s Hospital, Symonds Street, 1899

Collegians at Middle Gate, Winchester Colleg

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here