Focusing on the history of one place has its upsides, but there are rewards for looking more widely, sharing with other local historians and exploring the national context, writes Barry Shurlock

ONE of the joys of local history is that it brings alive communities and gives them meaning. The people who lived in the past become more real, and their houses, farms, churches and chapels get a personality.

But once the story of a place has been more or less mapped it’s useful to look at other places, to compare and contrast. After all, ‘local history’ is an oxymoron – no history is completely local!

Some places stand out for an event that made them ‘famous for five minutes’, but the stories of most overlap. Hence, the way that historians of one place have analysed, say, its manorial court, or its poor law, can be very valuable elsewhere.

Sharing information is getting easier as more local groups digitize their records and post them online. With the help of designer Tim Underwood, Milford-on-Sea Historical Record Society, founded in 1909, has just done this: 150 articles published in its Occasional Magazine are now online in its ‘Local History Lives!’ project (https://www.milfordhistory.org.uk).

For looking more widely a great portal is The British Association for Local History (BALH). It holds real and virtual meetings, runs blogs and publishes The Local Historian.

There is also a fascinating article in the latest issue by Winchester resident and retired BBC engineer Dr Albert Gallon based largely on material in the Hampshire Record Office. It tells the story of the Morant family of Brockenhurst, ‘of humble origins’, who settled in Jamaica and made a fortune in slavery and the sugar trade.

Other topics include ‘travellers’ in 17th century Devon, the role of wartime male voice choirs in Cornwall, the Peasants Revolt of 1381 in Essex, and press coverage of a new nuclear power plant 1955-1965.

BALH also publishes Local History News, a window on the work of local historians nationwide. It’s a great outlet for placing notices of local publications or projects and liaising with other groups.

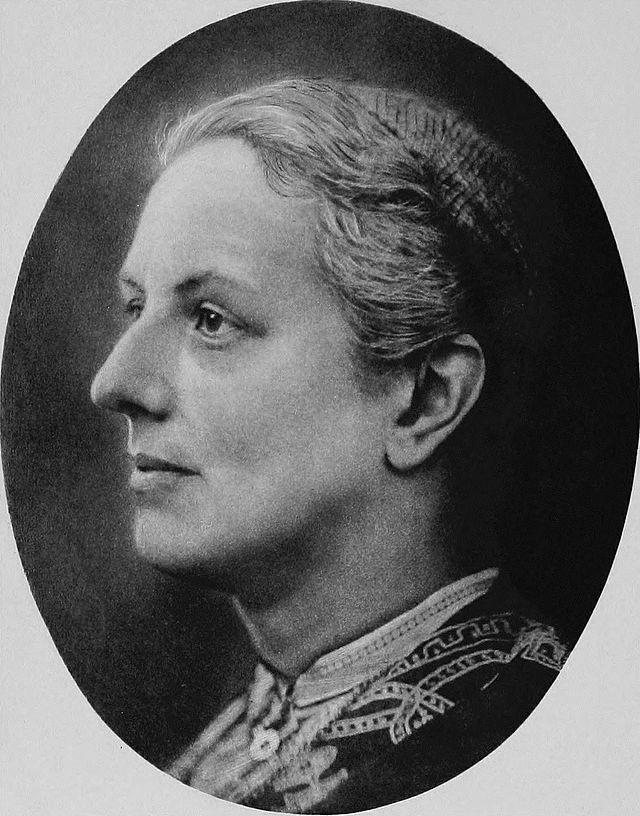

In the current issue Southampton historian Dr Roger Ottewill covers the bicentenary next year of the birth of Hampshire author and Otterbourne resident Charlotte Yonge (contact: alys_blakeway@yahoo.co.uk). There are also pieces on Lambeth Palace Library, methods for creating a ‘fun-trail’ based on local history, an ‘essential list’ of books for local historians and much else.

For many local historians, researching their own patch may be the first time they have looked at the past in any detail, since long-forgotten school lessons and dry textbooks with no apparent link to everyday life.

Even graduate historians of the old school have often only read the key texts, with little or no work on the bed-rock of history – that is, original documents. In contrast, almost all local historians start with original sources – parish registers, vestry minutes, churchwardens’ accounts, estate records and the like. There is a huge collection of such material in the Hampshire Record Office.

This brings history alive – with acerbic comments by clergymen, letters between tenants and landlords, court papers, and those rare ‘memoirs’ that were never published, which are the stuff of real history!

Original sources give a deeper understanding of a place – the factors that drove it, the characters who formed it, the geophysical factors that limited it or allowed it to flourish. This is when studies of ‘what happened’ move into the fascinating territory of ‘why’ and ‘what if’.

Rediscovering ‘dry textbooks’ may be part of the game, seeking national explanations for grassroots events. It’s a case of ‘bottom up’ meeting ‘top down’, with the potential for profitable links between local historians who have the detail and professional historians who have the big picture. The amateur may better understand the context of local events and the professional learn that standard teaching does not always stand up.

A rich vein for fleshing out local stories is, of course, national politics, especially in the Victorian period when so much changed. Its legacy for being ‘stuffy’ is ill-deserved and there are now so many sources online.

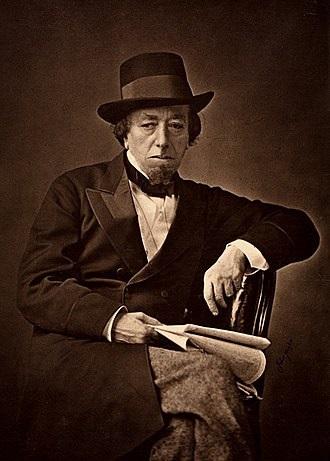

First, there is Hansard – the official record of parliamentary debates for the last 200 years or so. The idea that such debates should be publicly available was only accepted in the early 19th century. The heroes of free reporting were John Wilkes and later William Cobbett, helped by printer Thomas Curson Hansard, who as a result spent three months in prison. In 1812 Cobbett faced financial ruin and gave Hansard the rights to his Parliamentary Debates.

The History of Parliament online is also very useful, not only for parliamentary affairs but also for profiling the MPs and others who participated. To take but one example, you can learn that by the 1840s the Hampshire banker Alexander Baring owned 60-70,000 acres of land, but was in the habit of ‘scattering his purchases … to enable him to “elude the public eye” ’.

Then there are newspapers, now available online in the British Newspaper Archive (by subscription or free in the Hampshire Record Office and all main public libraries). One of the fascinating results of trawling these sources is an awareness that Victorian politicians faced problems and difficulties that are in many ways similar to today’s.

The big subject was ‘reform’ – how best to have an equitable system of representative democracy (still current with photo ID!). It was inched forward by means of thousands of hours of debate, with administrations succeeding or falling for what seem trivial reasons.

One of the heavweights, Disraeli, was reported to have confessed at a dinner in Edinburgh in 1867 that, despite his public opposition to reform, he had in fact been a secret advocate of everyone having a vote, but had taken a stance against the idea to instill it into the minds of his colleagues!

He later refuted the report, but the damage was done with the reported words: ‘I had to prepare the mind of the country, and to educate – if it be not arrogant to use such a phrase – to educate our [Tory] party. It is a large party and requires its attention to be called to questions of this kind with some pressure.’

There were many other matters that required ‘education’ of the country. These included the rights of non-Anglicans (Jews, Catholics and nonconformists) to public office, the secret ballot, a dignified arrangement for nominating candidates for election, ecclesiastical titles (Catholics forbidden to designate a Bishop of Winchester) and the like.

There was an end to execution in public and transportation to the Colonies, the ability to get divorced without an Act of Parliament, the end of land ownership as a qualification for MPs and the wealthy buying military commissions and much, much more. It’s a fascinating read!

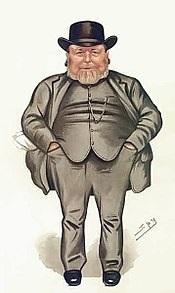

Newspaper reports in particular bring to life people like the Methodist preacher Joseph Arch, who in 1872 he founded the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, something that the Swing Riots of 1830 failed to do.

Commenting on the news, an MP of the time wrote: ‘Most persons had supposed that a race of beings brought up for generations under the exclusive tutorship of the landlord, the vicar, and the wives of the landlords and vicars, would have had any political tendencies they possessed drilled and drummed into the grooves of Toryism.’ Not so.

Arch was, however, operating in Warwickshire and it would be very interesting to know how his ideas were received in Hampshire. It’s just one of many new adventures that local historians can enjoy by making a New Year’s resolution to take a wider view.

Correction: a statement last week on Will Hall Farm should have read: ‘from at least 1484 until 2003 it was owned by Winchester College’.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

CAPTIONS

Barry Jolly (far right), MOSHRS editor for 10 years, in ‘Local History Lives!’ meeting

Hampshire’s forgotten author, Charlotte Yonge, born in 1823

Thomas Curson Hansard, publisher of parliamentary debates

Tory PM Disraeli, secret advocate of Reform

Joseph Arch, pioneer of unions for agricultural workers. Image: Spy in Vanity Fair

ends

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here