Fresh insights into the English Civil War come with a new book based on the story of the fall of a Hampshire stronghold that, like Winchester, held out for the king, whilst most of the county declared for parliament, writes Barry Shurlock…

IN some quarters, the death of Queen Elizabeth II and the accession of Charles III have encouraged republicans to contemplate a time when the country is no longer headed by an individual who inherits the right to rule and the benefits of huge wealth and possessions.

Polls indicate that about two-thirds of the whole population supports the monarchy, but only about one-third of people aged 18-24 years share the same sentiments. Even the Meghan and Harry story demonstrates royals stepping aside.

For historians, such trends evoke the Civil War of 1642-1649 – now often called The War of the Three Kingdoms - and the Commonwealth of 1649-1660, which is one of the toughest periods of history to fathom. Trying to understand why the war started, what happened and what it all meant is far from easy.

And even when the story seems to be clear, a new piece of information may appear to cloud it over again – like the painter who makes ‘one last touch’ to a picture, only for it to look less convincing.

One such very large piece of information is a new, Hampshire-based book by best-selling author Jessie Childs, The Siege of Loyalty House (Bodley Head). This ‘thrilling immersive read’, as Simon Schama calls it, is centred around the sieges of the royalist stronghold of Basing House, near Basingstoke.

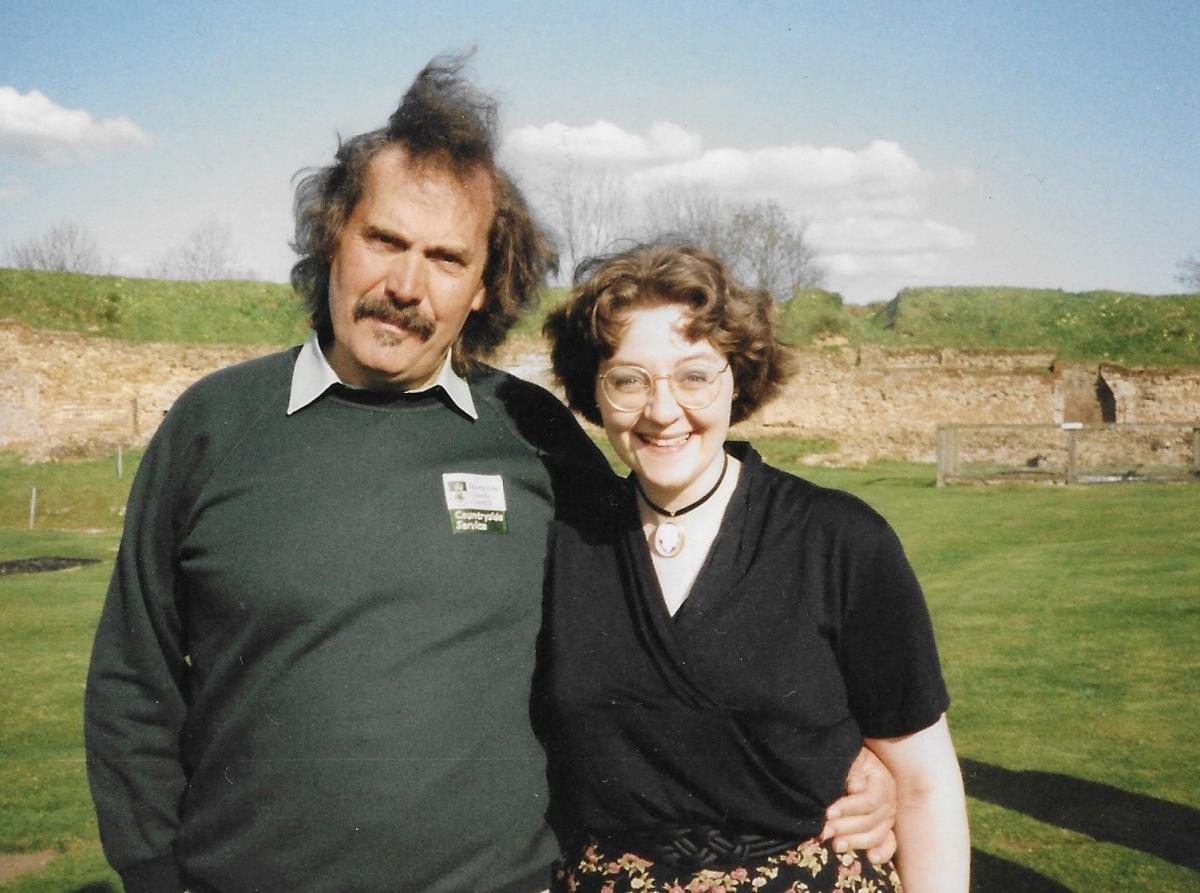

She acknowledges help from Alan Turton, who was the site’s curator for 24 years and lived with his wife Nicola ‘above the museum’. He comments: ‘Hampshire was generally for the parliamentarians, though Winchester was royalist because of the cathedral. The king was his own worst enemy, but they did not set out to kill him – [the parliamentarian] the Duke of Essex in fact defended him.

‘But there was no coherent idea to set up a republic – it was more a series of experiments in government. It might even have continued with Oliver’s son Richard, who was a sensible man, but he couldn’t pay off the Army.’

Nicola reviewed the new book recently for the Basingstoke Archaeology and History Society, citing the parliamentary lawyer Sir Bulstrode Whitelock’s words: ‘It is strange to note how we have insensibly slid into this beginning of a civil war by one unexpected accident after another…’.

The Siege of Loyalty House not only tells the long story of how the house and royalist stronghold of the Marquess of Winchester became a symbol of the struggle between monarch and parliament (yet it was, after all, only a grand house!), but also shows how it affected many people in the county who were otherwise uninvolved.

For a start, the Marquess set fire to his estate cottages to avoid giving the besiegers shelter. He also took money from local people to support the garrison, a burden that Mistress Zouch, ‘the unhappy widow of a royalist colonel’ living in Odiham, could no longer endure.

John Atfield of Basingstoke was also in trouble about land leased from the Marquess at Kingsclere, where he had built two new mills and a ‘maltmill’ at the cost of £200, but had lost all proof of his tenure as his ‘goods and writings’ had gone up in smoke with his house.

The almsfolk of St Mary Magdalen Hospital, Winchester, who took no side, were also devastated. They had 36 sheep stolen by royalists, then in a second pillaging lost ‘all their seed barley and every bit of wood [for fires] – the gates, doors, wainscot, tables, cupboards, even the pews and communion table in their chapel’.

All this detail adds flesh (often literally) to what is otherwise – to modern eyes – a merciless struggle between intransigent factions. Even within Basing House there were two distinct camps that held two different religious services – the Marquess’s Catholic supporters and the royalist military commander and his soldiers: they were protestants, but different from parliamentary protestants, who embraced puritanism and rejected the authority of bishops. You get the muddle!

The outcome for the country from 1649 was Commonwealth rule, with a rump parliament and Council of State, followed by the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell and briefly (274 days) of his son Richard, who lived at Hursley before fleeing abroad for 20 years.

One of the strengths of Childs’ new book is that she lathers on a mass of wide-ranging facts, so that readers are given the chance to reach their own conclusions. She covers the lead-up to the start of the war in London, and follows through with blood and guts accounts of the three parliamentarian sieges needed to overcome the Marquess’s garrison at Basing House.

There are charming cameos of some of the royalists crammed into Basing House in the most awful of conditions. These include the endless scribbler Thomas Fuller, still known for Fuller’s Worthies, published posthumously in 1662 and laced with colourful sketches of Hampshire, ‘a happy county’. The architect Inigo Jones was also there and many others.

The assault of November 1643 led by Sir William Waller failed three times to take the house and he decided to fall back for the winter to the neighbourhood of Odiham and Farnham. The royalists had a similar plan – to hole up in Winchester, Alton, Alresford and Petersfield.

But Waller seized the initiative at Alton and with ‘a stealthy across-country approach and a lightning strike’ vanquished the troops, who were forced to retreat into the church, where many were killed. The doors still bear witness to the musket shot! Three months later the royalists were also left reeling at Cheriton.

The next year parliamentarians set up a sneaky plot with the Marquess’s younger brother, Charles Paulet (or was it Edward, the youngest brother, Childs queries?), to arrange a surrender, but it was discovered –the ‘traitor’ survived, but not his accomplices.

In June 1644 the parliamentarians attempted to starve Basing House into submission, but a relief army led by the genius Sir Henry Gage heroically broke though the lines and resupplied the house. The truly horrifying injuries sustained by the parliamentarians are detailed in the book. One man had a five-inch laceration above one ear, sword wounds on stomach, hip, groin and a hand, which was ‘half off’. Little hope, you might think: but he survived, probably because bacteria were eaten by maggots.

One of the casualties was Thomas Johnson, a Royalist lieutenant-colonel and ‘father of British field botany’ who died a fortnight after being shot in the shoulder. As Childs puts it, he died during the siege ‘in a farmyard full of squealing pigs and howling men’.

It was only in October 1645 that the house eventually fell, when Cromwell – fresh from taking Winchester Castle – arrived with heavy guns and granadoes (a type of nail bomb) and successfully stormed the garrison. It was a messy end (witness a decapitated skull found in 1991) when what Cromwell called ‘a nest of Romanists’ were rooted out by the simple measure of blasting great holes in the walls of the house.

Childs’ book will add greatly to the canon of works on the period. The classic book on the subject published in 1882 is The Civil War in Hampshire by the Rev. George Godwin, son of a Winchester draper, Chaplain to the Forces, and one of the founders of the Hampshire Field Club.

His title was reused in 1999 by Tony MacLachlan. Other sources are The Civil War in Winchester by Richard Sawyer (2002) and Cheriton 1644: the Campaign and the Battle (1973) by John Adair. A valuable account of the Battle of Cheriton by Mark Tippett appears in Alresford Through Time, published recently (publications@alresfordhistandlit.co.uk).

It’s not too late to tuck the new book in someone’s Christmas stocking and possibly help them get a better understanding of this tumultuous period. But that could change soon, when OUP publish a multi-volume work, The Letters, Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here