Government direction of agriculture in wartime Hampshire had some successes and a terrible tragedy, writes Barry Shurlock…

CURRENT events in Ukraine are unlikely to lead to food shortages in the UK, but if they did Whitehall could look at how the country coped during the last two world wars.

As it happens, some events in Hampshire concerning the production of food during 1939-1945 have entered the history books and become subjects of serious research.

Perhaps the most iconic of these is the killing in July 1940 by police of a small-time farmer in the upper Itchen valley for failing to plough up grassland.

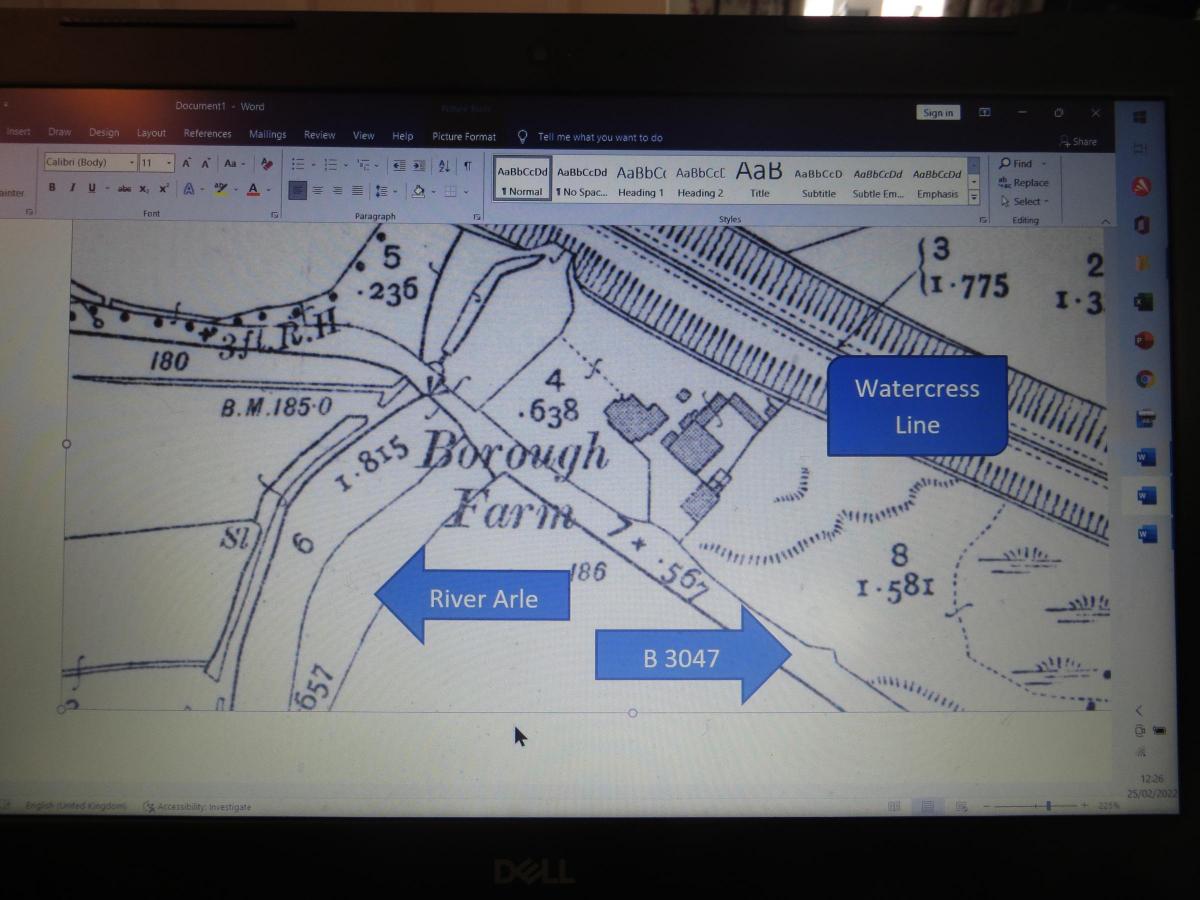

It occurred near Itchen Stoke – though actually in the parish of Ovington, as it then was – beside the Alre, where it mingles with the Candover and the Itchen in beautiful otter-bearing water meadows. This idyllic part of the county had long drawn celebrated admirers, such as the writer W.H. Hudson and the Foreign Secretary Lord Grey of Fallodon.

Known as the Siege of Borough Farm, the event involved a smallholding then on the Tichborne Estate being farmed by George Raymond (‘Ray’) Walden. One of the best studies of the affair is by Professor Brian Short, University of Sussex, in the Agricultural History Review, where he calls it “the best-known individual farm dispossession case of World War Two”. His book Battle of the Fields is a key study of wartime agriculture on a broad front.

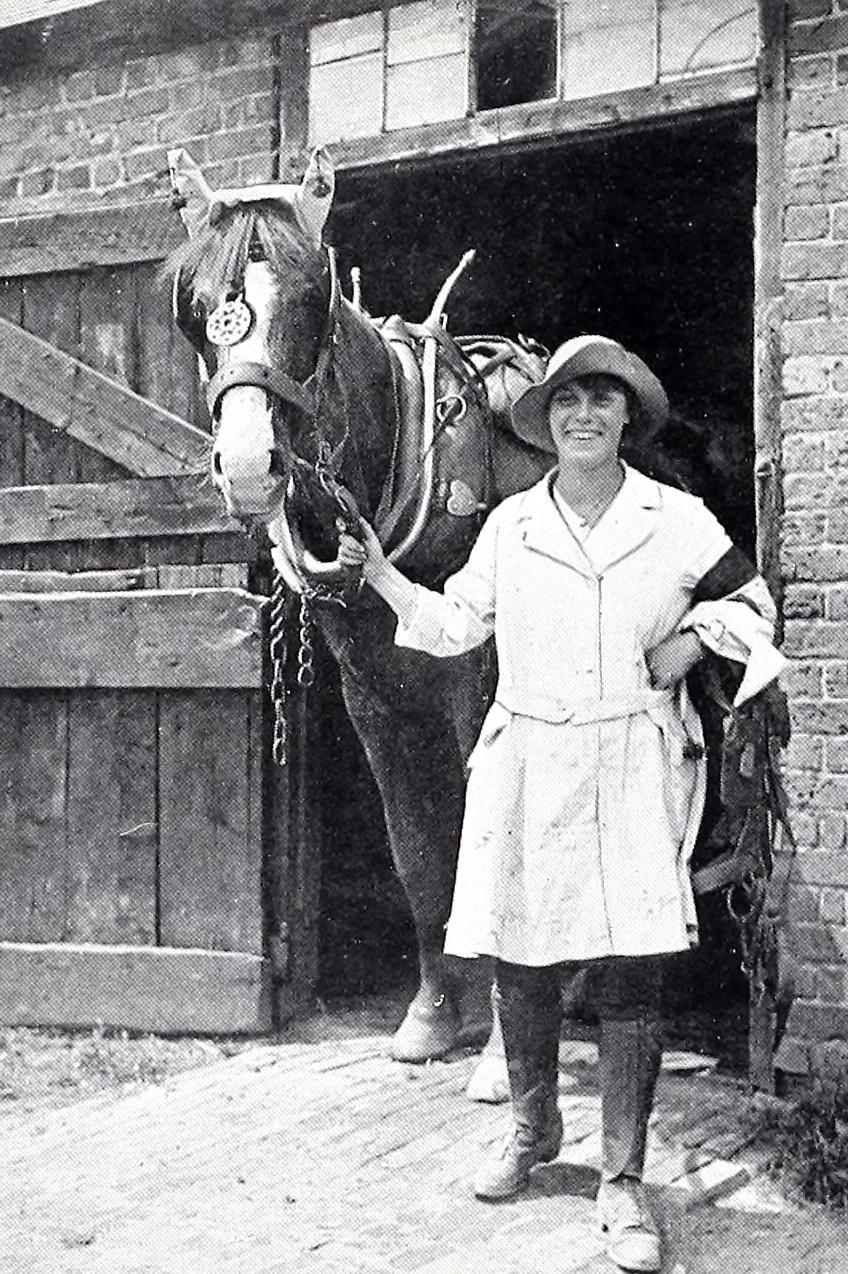

Shortages of food in both world wars led to the creation at the county level of War Agricultural Executive Committees, known as ‘War Ags’ which had draconian powers to force farmers to cultivate their land in a way that was judged best for producing given foodstuffs. The Women’s Land Army also had a crucial role.

Ray had inherited the lease of a “small, inconvenient and old-fashioned farm” where he kept horses for contract ploughing, a small herd of cows and bred “good quality pigs”. He was a bachelor, had hardly ever travelled anywhere and, according to an account by local historian Jane Underwood, was “rather crotchety in business deals”.

In 1940 he was instructed by the Hampshire War Ag to plough up 34 acres, 55% of his land (often reported in error as 4 acres), which would have been a disaster for his animals. He therefore refused and on 7 July he was served with seven days’ notice of eviction, which he ignored.

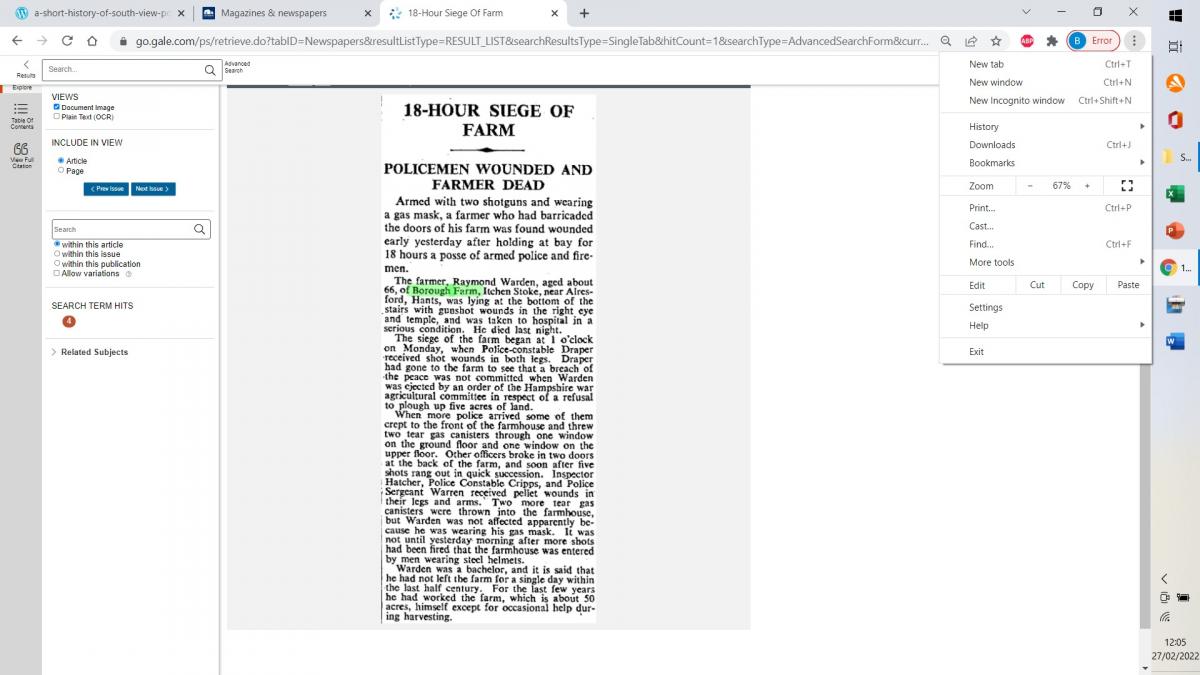

On 22 July John Morton, the Assistant County Land Officer, was sent with two PCs to take possession of the farm. But Ray was armed with a shotgun and resisted. At one point in an 18-hour siege he let off one of his barrels at PC Reginald Draper from Ropley, injuring him in both legs and an arm.

The Police were now dealing with a case of attempted murder and had no option but to go in in force. Tear gas was tried, but didn’t work as Ray possessed a war-issue gas-mask! Eventually things got to such a pitch that he cried: “You are going to kill me, or I am going to kill you. I am not going to give in.”

In the final assault he was found lying on the ground and died later in the Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester. In the inquest, at which the policemen testified, a jury returned a verdict of justifiable homicide. One press report headlined it: “P.C. in court on stretcher”.

Clearly, this was a terrible affair, and the story made the columns of the Chronicle, as well as the national press, in The Times and Daily Mirror and many other newspapers as far afield as Belfast and Dundee. Surprisingly, in the immediate locality “the whole operation was hardly noticed at the time” according to Jane – and even today there are few local residents in the upper Itchen valley who know the story.

In the following years Ray became something of a martyr and A.G. Street dedicated his novel Shameless Harvest to him. Undoubtedly it was a very sad story, and in his study Brian Short concludes that the actions of the War Ag were, indeed, ‘harsh’ and ‘disproportionate’. But in the early days of the Battle of Britain the death of this small-time farmer from Itchen Stoke was regarded as ‘a misfortune of war’.

The same study covers several other disputes that highlight the shortcomings of measures to maximise wartime food production in the county, though without tragic outcomes.

John Crowe of Ashe Manor Farm near Overton was given three weeks to quit for a late return of a form. Rex Patterson – a celebrated innovator of the outdoor bail system of milking – became embroiled in arguments about his practice at Hatch Warren Farm – now lost in the urban sprawl of Basingstoke. It even reached the floor of the House of Commons.

At one point the penalisation of such pioneering farmers and other matters brought conflict at the top. The vice-chair of the Hampshire War Ag, Roland Dudley, a mechanisation pioneer from Linkenholt, resigned.

The full story of food production throughout the country in the world wars has been told in the BBC series Wartime Farm, presented in 2012 by archaeologist Alex Langlands and others. More locally, a detailed account of the Hampshire War Ag can be found in the Romsey Advertiser (April 3, 1942) in an article first run in the Daily Herald.

It is one of many nuggets being researched by Romsey historian Phoebe Merrick, who is undertaking the time-consuming task of trawling through every edition of the Advertiser during the war years.

The account claimed that Hampshire’s War Ag, which worked with 7,000 farmers – 4,000 of them farming less than 50 acres – was “the most go-ahead” in the country. Before even hostilities started, every farmer had been given a plan of their land and “told how best it could be cultivated and what crops could be grown”.

Six District Committees of local farmers decided in detail how best to improve production in farms in their areas, assessing ‘the power’ of a farm on the basis of: “one man counts as one unit. A woman counts as two-thirds of a unit. Old men and casuals are given a lower unit value. Four horses count as one Fordson tractor, and one tractor is one power unit.”

It worked out that on average a farmer with 60 acres of ploughland and 120 acres of grass should have been able to farm effectively with ‘the power’ of one tractor or four horses. Three acres of grass needed the same power as one acre of ploughland. The system also allowed the War Ag to decide if a farmer’s claim for a new tractor, supplied with public money, was justified.

Public money helped farmers in many other ways: “If a farmer wants to buy a stationary engine or needs a permit for wire netting it is found for him. If he needs sacks or permits to purchase material they are found. Two exceptions are material for bomb-damage building repairs and coupon-free protective clothing.”

There is yet another link of War Ags with Hampshire, as the idea had originally been developed during WW1 by the 2nd Earl of Selborne, who had a large country estate in the county at Blackmoor, near Liss. In a note marked SECRET and held at the National Archives, he argued that “much could be done to organise an increase of production”. Apparently one pressing problem was a shortage of men “to work steam-ploughing tackle”. How times change.

For more on Hampshire, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk, and www.hantsfieldclub.org.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Message from the editor

Thank you for reading this story. We really appreciate your support.

Please help us to continue bringing you all the trusted news from your area by sharing this story or by following our Facebook page.

Kimberley Barber

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here