SOME schools have a ‘honours’ board with the names of ex-pupils who have ‘made it’. There might be an MP or two, a bishop, a successful businessman, perhaps a pop star, a footballer, or a TV personality.

Others have so many renowned ex-pupils that to honour them in this way would require the entire wall-space of the school hall (rather like the names of Hampshire’s MPs on the wall of the Great Hall, Winchester).

In this category is Winchester College, whose glittering alumni need commodious websites such as ‘List of Old Wykehamists’ on Wikipedia. These, of course, are all men, but women – or alumnae – will surely start to appear after the school takes girls from next year.

Understandably, public schools are particularly proud of any prime ministers they produce. Winchester has had only one, Henry Addington (1757-1844), though few people will have heard of him. Whilst at the school he formed a close link with his master, George Huntingford, a Winchester native of relatively humble origin, subject to much snobbery.

Addington became PM in February 1801, after Pitt the Younger left office, exhausted and weakened by drink. As George III put it: “If we three do but keep together, all will go well.”

However, George Canning, who had started his education at Hyde Abbey School, Winchester, before going on to Eton, had other views, which he penned cattily as:

As Pitt is to Addington,

London is to Paddington.

The two men had been close friends: for 12 years Addington had been Speaker under Pitt. But Canning’s words proved truer than the king’s. As the threat of invasion by France mounted, with Hampshire militia lined up on the coast, the friends fell out. Pitt returned as PM in June 1803, “back, but never the same”, as William Hague put it in his masterly biography.

Ennobled as Viscount Sidmouth, Addington in fact outlived Pitt by many years and went on to occupy a variety of government posts. However, as regards PMs, the Winchester record pales beside that of Eton, a school that in 1440 was in fact set up as a copycat of William of Wykeham’s model. To date it has spawned no less than 20 ex-pupils in the top job.

The Eton-Winchester rivalry came to the fore in parliament in 2019 when Old Etonian Jacob Rees-Mogg described a comment by Wykehamist Nick Boles as “highly intelligent, but fundamentally wrong”.

As regards chancellors of the exchequer Winchester has, however, done rather well, with six incumbents, including the current one Rishi Sunak. Henry Addington himself also held the post as well as being PM. Later came Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke (1811-1892), who had the job under Gladstone, but is judged a failure by historians for being too stingy, underestimating revenue and denying tax cuts.

Other chancellors include Stafford Cripps, a socialist with a deep Christian belief. At school he excelled at Winchester Football (the school’s own game and still played), and also science, even winning a scholarship in the subject to New College, Oxford. But he did not take it up, preferring to follow law, and building up a very successful practice.

He entered parliament late in life and was appointed chancellor in the turbulent times of 1947. He advocated nationalisation, generous spending on welfare and a programme of building no less than 200,000 houses. The next chancellor, Hugh Gaitskell, was also a Wykehamist, who had distinguished himself as an oarsman and won several school prizes, in history, divinity and other subjects. His political credibility was marred by being the first to suggest that patients “should pay a modest charge for some dental work and optical services”.

The next Wykehamist to be chancellor was Geoffrey Howe, satirised by Dennis Healey as a ‘dead sheep’, though one who later delivered a resignation speech that did much to finish Margaret Thatcher’s premiership.

As well as these top jobs, Winchester has produced a huge number of people who have made their mark elsewhere. In the nineteenth century alone more than 130 names would have to be put on any honours board. This in part reflects the fact that the school then expanded hugely from its original 70 scholars. There were always ‘paying’ pupils without scholarships – called ‘commoners’ – but the 1860s saw a huge expansion, with ten new boarding houses, each for 60 boys. Today the school has nearly 700 pupils.

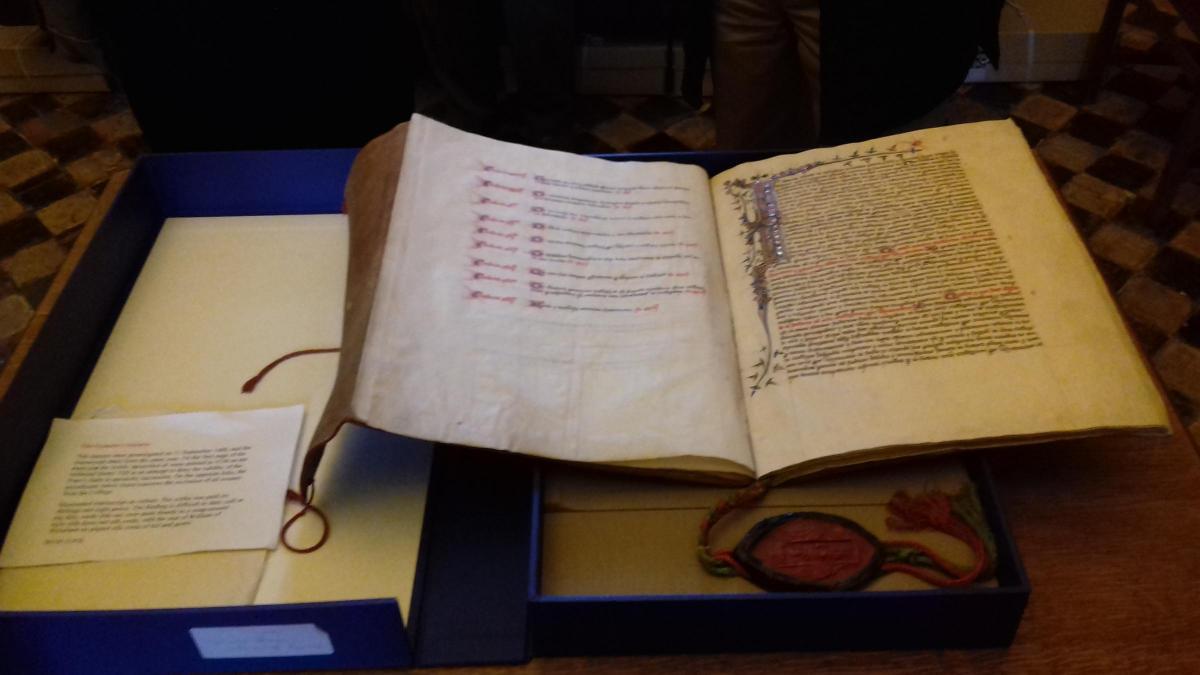

Even before the school was formerly founded in 1381, its potential had been demonstrated. Henry Chichele, who went on to become Archbishop of Canterbury “is thought to have been one of the boys maintained by Wykeham under the schoolmaster he set up in the parish of St John’s” before the foundation, according to College Archivist, Suzanne Foster. Over the years there were several other Wykehamists who took the job, as well as numerous bishops. In fact, in the school’s early days, most of its distinguished pupils were either churchmen or lawyers.

There were, however, a few oddballs, such as Thomas Coryat, Court Jester to James I, and Henry Garnet, a Jesuit priest executed for his part in the Gunpowder Plot. In general, however, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not the school’s grandest hour. There was the odd playwright, like Thomas Otway, two poets laureate and an undistinguished Speaker of the House of Commons, Charles Wolfran Cornwall, whose huge monument in the chapel of the Hospital of St Cross, Winchester, tries to make a grand statement.

The nineteenth century fared better for the school. It produced its first and only well-known novelist, Anthony Trollope, who was there briefly in 1827-1829. He was also educated at Harrow. Other celebrated Wykehamists from this period include the politician Lord Grey of Fallodon, Arthur Pearson founder of the Daily Express, the pure mathematician G.H. Hardy and historian Arnold Toynbee. The school also produced the Fascist leader Oswald Mosley and John Druitt Montague, one of those suspected of being Jack the Ripper.

It is perhaps too early to judge how the school fared in the last century. But already on the list are well-known figures such as art historian Kenneth Clark, politicians Willie Whitelaw and Richard Crossman, personalities such as Tim Brooke-Taylor and Robyn Hitchcock, and the fly fisherman GEM Skues. Also, someone who made a huge contribution to modern life, but is hardly known, the winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, Richard Synge, who pioneered the analytical techniques of chromatography (google it!).

Whether Rishi Sunak will double the number of prime ministers educated at Winchester College remains to be seen. The FT headlined his third budget “Fizzy Rishi plays politics”! Certainly, the bookies are hopeful, with him recently leading the odds at 7/2, ahead of Sir Keir Starmer, 5/1, Michael Gove, 13/1, and Jeremy Hunt 17/1.

For more on Hampshire, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk, and www.hantsfieldclub.org.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here