THE recent success of the Chesil Theatre in progressing plans for the expansion of its premises in Winchester is great news for theatregoers and a tribute to the heroic efforts of those who since 1998 have worked to make it happen.

The adaption of the redundant church, St Peter’s Chesil, which opened in 1966 to provide an intimate venue for drama in the city, is a crucial chapter in the history of theatre in Winchester. It was unrivalled in recent times until the rebirth in 1978 of the Theatre Royal, which has been chronicled by Madelaine Smith and Phil Yates in Behind the Curtain.

‘The Chesil’ has been so successful that it has probably obscured the fact that its governing body is the Winchester Dramatic Society, a private company limited by guarantee without share capital – meaning that any profits go back into the coffers.

Its story is an essential part of treading the boards in the city and has been told by Lisbeth Rake in A History of the Winchester Dramatic Society. It is a great contribution to the progress of theatre in Winchester, but, the full picture over time is more tortuous and in itself a dramatic performance.

The distinguished theatre historian Paul Ranger mapped the story of drama in Winchester in a paper on ‘lost theatres’ published by the Hampshire Field Club. He put the start in the 10th century, when at Easter monks ‘in drag’ played the visit of the holy women to the Sepulchre and an angel announced the Resurrection. There are even surviving stage directions and descriptions of the costumes.

Later, drama moved out of churches and onto wheeled platforms that might be set up at key places such as the Buttercross to play cycles of morality plays and other tales. After the Reformation, bands of wandering players, like those in Shakespeare’s time, would arrive in the city and seek the permission of the mayor to perform.

The first theatre venue of any kind was in The Square on the upper floor of the shambles or meat market, on the site of what is now the City Museum. Ranger depicts it as “squalid…smelling of carnage and animals…with shouts of vendors... and vagrants being publicly whipped”!

In fact, despite the unpleasant setting audiences were often good, especially during race week and when pillars of society attended, such as the Duchess of Chandos from Avington Park.

The militia were also avid theatregoers and during the Seven Years War (1756-63), when troops camped in Winchester, a temporary theatre was built with “a pit, a low stage and a number of boxes”. Distinguished amongst officers in the city were John Wilkes, the champion of press freedom, and Edward Gibbon, author of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

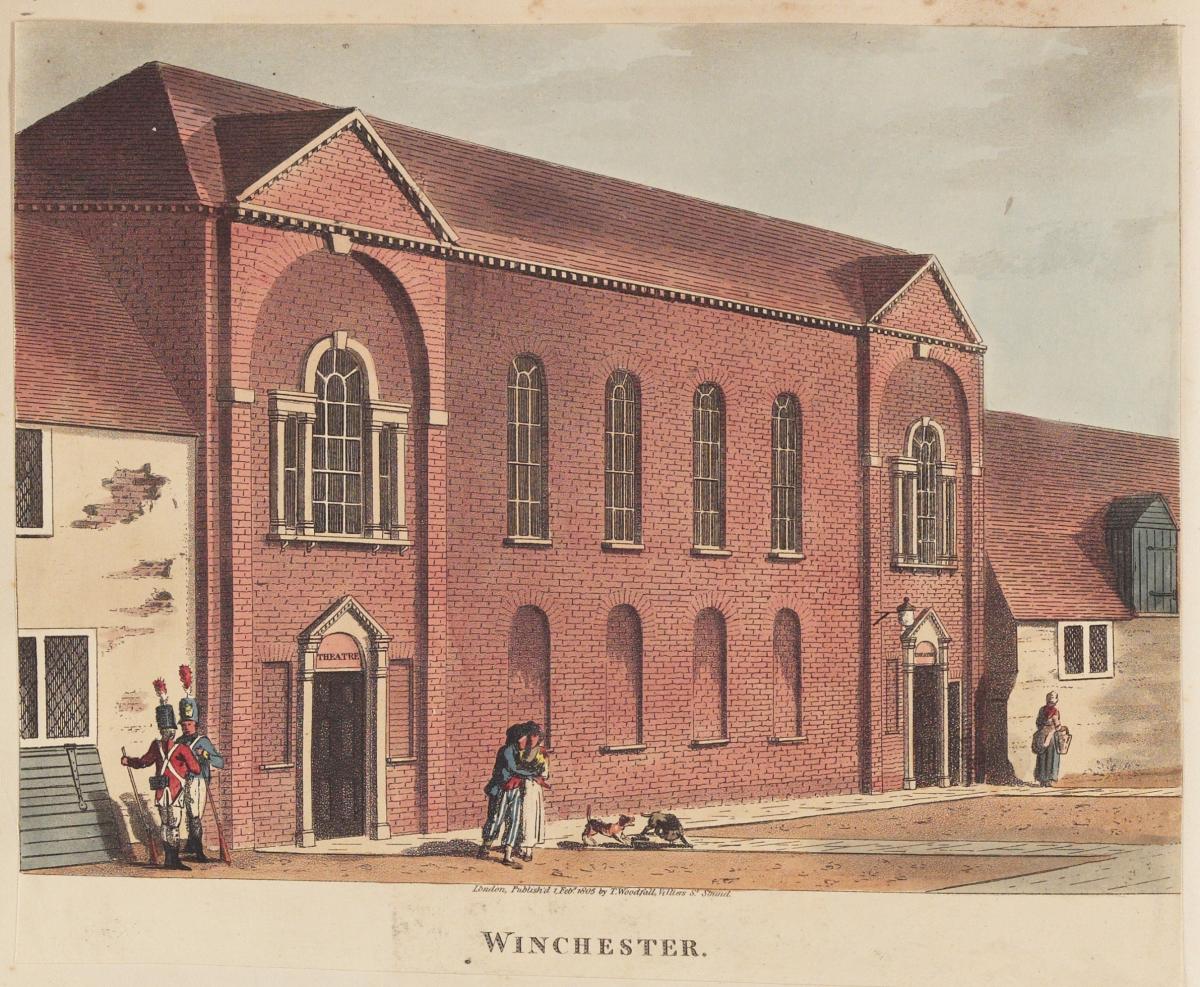

But Winchester deserved more! And in May 1785 it came in the form of a purpose-built theatre on Jewry Street, on a site now marked by Sheridan House, with one surviving window. The new theatre thrived for its first 20 years or so, boosted by its association with Winchester’s race-week. But by the 1840s – like theatres in Portsmouth and Southampton – it was up for sale. Heroic managements managed to keep it open, though the end finally came in 1861, when it was sold to a builder’s merchant. The Theatre Royal did not open its doors until 1914.

Just as drama left one professional venue it popped up in another, an amateur one, in St John’s House, where local brewers Hugh Wyeth, based in Hyde, and Giles Henry Pointer, in Cheesehill Street and elsewhere, reached into their pockets – and perhaps drew on their egos!

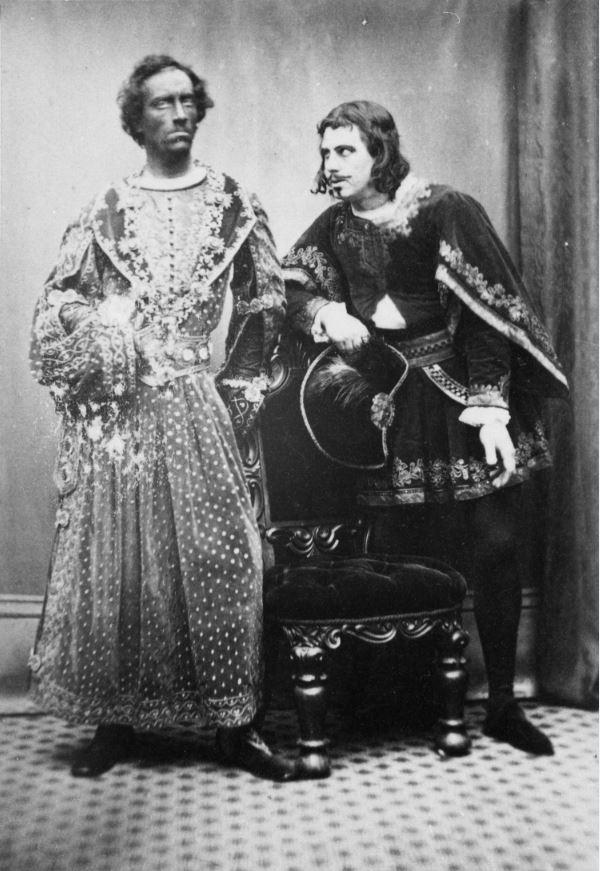

Hugh put on two entertainments in St John’s House with himself in leading roles. The Hampshire Advertiser reported that they were “an unbounded success to crowded and fashionable audiences”. Two years later in 1863 it was Macbeth, with Hugh playing the title role and Giles playing Macduff.

The Winchester Dramatic Society formally came into being in that year and ever since has given the city an astonishing repertoire of drama. Interestingly, for many years it had a fruitful association with the Winchester Mechanics Institute. This was established in 1835 to provide ‘the ordinary man’ (yes, no women!) with facilities to ‘get cultured’ – to read, listen to debates and lectures, learn to draw, play music or even learn Latin.

WMI and WDS worked closely together on the production of plays and the like until 1893, when an advert in the Chronicle announced that the latter had been “organized on a fresh and wider basis, which identifies the member with the city rather than the [WMI] as heretofore”.

An era had ended: in 1885 Hugh had, as he put it, bade “farewell to public histrionics” after his third production of Macbeth, and in 1890 fellow brewer Giles died. It also marked a long pause in WDS’s production of Shakespeare, since no account any of his plays is apparent until 1970.

Perhaps the performance in the city in 1889 of six plays by the company of noteworthy Shakespearian actor and Wykehamist, Frank Benson, had stunned the amateurs. He had grown up at Langtons, Alresford – on the corner of East Street and Sun Lane – and was knighted in 1916.

During its first 60 years, WDS often employed professional actors – including one manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane – to work alongside local amateurs, all men. Non-professional actresses did not perform until the late 1880s and for many years their names were ‘hidden’ at the end of the cast list, rather than being in order of appearance.

The male actors were drawn from well-known local stalwarts with a wide range of interests. They included the pioneer photographer William Savage, and the antiquary, proprietor of the Chronicle and later mayor, William Henry Jacob. Also treading the boards was architect and local historian Thomas Stopher, who with Jacob was a prime mover in the establishment of the City Museum.

WDS members played a huge part in the 1908 Winchester National Pageant, which was master-minded by Benson, with leads from Stopher and another architect, Bertram Cancellor, who, in 1912, was engaged to convert the Market Hotel into the Theatre Royal.

Other groups that at various times brought drama to the district grew up in Alresford, Shawford and Twyford, whilst those in the city included the Weeke Players (formerly the St Paul’s Amateur Dramatic Society), the West Downs Players, the St Maurice Players and others.

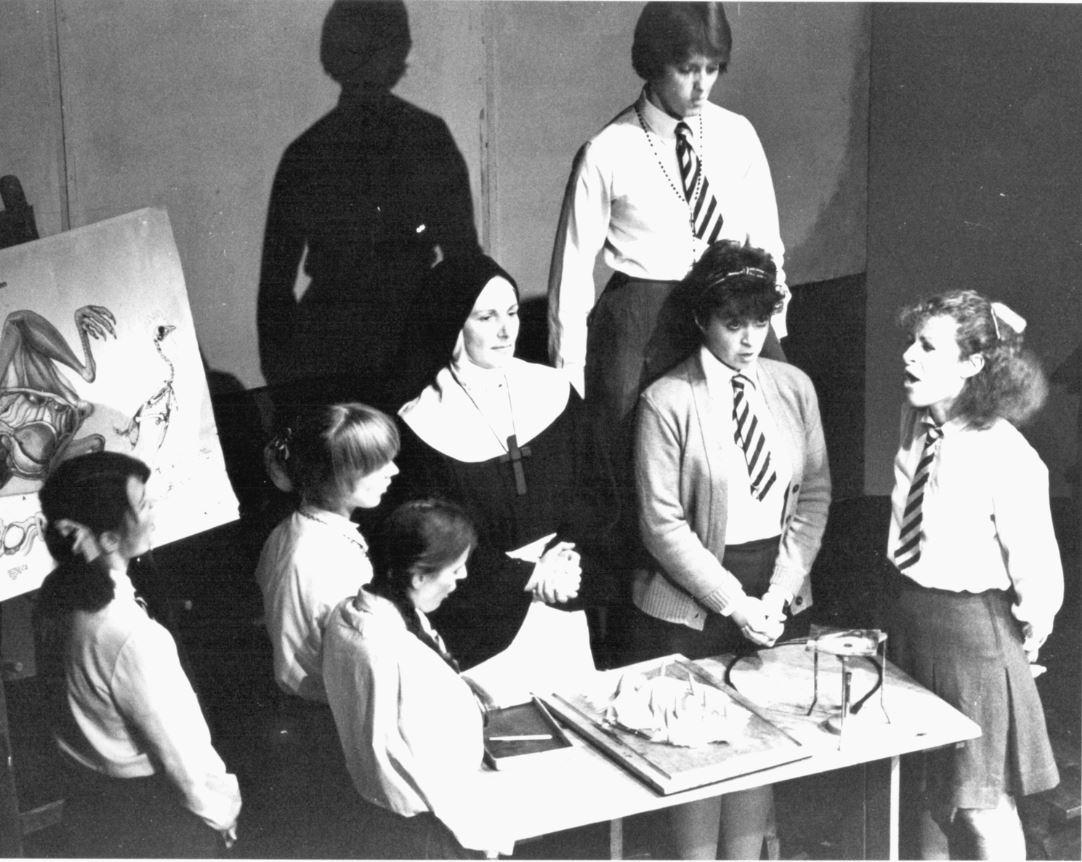

Lisbeth Rake’s A History of the Winchester Dramatic Society, available from flavia.bateson@starspray.org, tells the story up to modern times, with some surprising incidents. In 1985 WDS decided to put on Mary O’Malley’s Once a Catholic, but it was banned after its first night by the Bishop of Winchester, exercising his prerogative on the use of St Peter’s Church. For a provincial theatre it was a gift. The national press descended, the show was transferred to the Tower Arts Centre in Romsey Road and was a sellout.

Another gift was Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which in 1996 was on at the National Theatre. WDS was denied the rights to stage it – on grounds of competition! Secretary Mavis Ricketts decided to go straight to the author and soon her husband was handing her the phone with the words: “It’s Tom Stoppard for you.” Problem solved.

The Chesil archives, which are in Hampshire Record Office, were catalogued some years ago by Tony Dowland. Looking to the future, current archivist, Flavia Bateson, said: “That Chesil Theatre can mount major productions that variously entertain, inform and enlighten, yet on budgets a fraction that of professional shows, is due to the substantial donations in time, energy and expertise made by the volunteer members.”

For more on Hampshire, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk and www.hantsfieldclub.org.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here