YOU may pass them on a Covid walk without realising what they are. They look like perfectly normal houses – even fine ones – but they were built with unconventional materials.

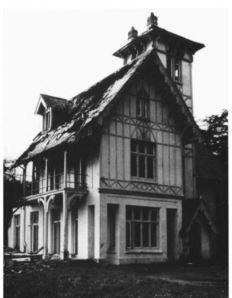

These are the numerous houses made of chalk. There are many examples in Hampshire, especially in and around the Test Valley and between Andover and the Salisbury Plain. They include Rookwood School in Andover, which was built as a fine gentleman’s residence and Thimble Hall, Quarley, originally a pair of cottages.

A fine example once stood where the Royal Hampshire County Hospital was extended in the 1980s. Many existing houses in the Orams Arbour and St Cross areas of Winchester are also made of chalk, excavated from local railway cuttings. And yet from the outside you would never know it.

In many places, especially in the river valleys, there are long stretches of chalk walls, sometimes with thatch toppings but more recently tiled. As well as acting as boundaries these rammed chalk walls encouraged early fruiting of fan-trained fruit trees – remnants of the timbers that held the wires can still be found.

A village that has more chalk buildings than any other in the county is Kings Somborne, where historic buildings expert Gordon Pearson lives. Now retired, he spent much of his professional life studying ‘earth structures’, as they are called, and working to preserve them.

A prolific author, he has written more than 100 papers on local history, as well as two books, The History of Up Somborne and Rookley and The Revd Richard Wake (1831-1915): Somborne’s Pioneering American Colonist, a biography of the founder of Wakefield, USA.

His Conservation of Chalk and Clay Buildings is the standard work on the subject. When it was published in 1992 it took over from Building in Cob, Pisé and Stabilized Earth published in 1947 by the creator of Portmeirion, Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, and his architect colleague John Eastwick-Fields.

Essentially, there are two different techniques for using chalk in construction. The traditional method involves stamping down the material with added straw and water about a foot at time, allowing it to dry sufficiently for another section to be added, perhaps a week later. In this way walls to roof height can be built, though not gables and openings for door and windows have to be sawn out of solid walls.

Evidence for similar methods predating Roman times have been found and they lasted into the early twentieth century. In Celebrating Somborne, Gordon has described the processes in detail. Chalk was dug out alongside the walls or transported from pits nearby. Winter frosts helped to break up the chalk, making it ready to use in the spring. Horses were also used to smash up the chalk.

To provide a solid base a flint plinth was first laid, about 18 in. wide and a foot high. The chalk was broken into lumps of about 2 in. and these were mixed with dust to form a ‘well-graded mix’. This was mixed with straw and water to ‘the consistency of stiff dough’, which after leaving for a while was layered onto the plinth with a three-pronged fork.

It was then trampled down by ‘workmen wearing heavy iron soles strapped to their boots’. It was a laborious process that could only be carried out in the summer and the resulting walls had to be dried for a year before being coated with a chalk slurry.

In the late eighteenth century the architect Henry Holland discovered pisé de terre, a French technique for building in chalk. He first used it to build cottages on the Woburn Estate of the 5th Duke of Bedford and it soon became widespread in Hampshire and elsewhere.

It had the advantage of being much quicker and making stronger walls. There are several fine buildings made in this way in Kings Somborne, including the Methodist Free Church of 1826 (now a private dwelling), which Gordon calls ‘a superb example of a local building constructed by the pisé method’. Similar chapels were built in many other places, including Houghton, Timsbury, Middle Wallop and Kings Worthy.

Chalk was rammed down within shuttering, which was then moved up a stage at a time to take more sections. The walls were finished with ‘a soft lime-based render’ which is why such houses in urban settings, do not announce their method of construction.

There are good examples in Eastgate Street, Winchester. After the sale of the grounds of Eastgate House in 1844, houses were built on the corner and along the west side of the street, using chalk taken from St Giles’ Hill, according to Andrew Rutter, in Winchester: Heart of a City. As well as being convenient, it was probably a ruse to avoid brick tax, imposed in 1784 and not repealed until 1850.

Between the wars, chalk was also used in a utopian settlement at Quarley, near Andover. This was the brainchild of barrister Brinsley Nixon, who undertook the project to honour a friend who did not return from the trenches, simply called Hugh – his surname was never revealed.

Nixon chose to build houses and farm buildings in’ Hugh’s Settlement’ with chalk. Details from the 1920s and 1930s are in the Hampshire Record Office, Winchester and Jane Lambert has published articles on the scheme in Lookback in Andover, the journal of the Andover History and Archaeology Society.

Construction started poorly and architect Jessica Alberry – one of the first women to enter the profession – was called in. After several attempts, she abandoned the pisé method in favour of making blocks of chalk in the style of ‘adobe’. One fine thatched house made in this way and named after the architect, and later renamed Etekweni, burnt down in 1987, though others survive.

Elsewhere in the county, near Beaulieu, earth structures – albeit in traditional cob, with clay and straw – led to a completely new village. It began as a squatters’ settlement on forest land and was named Beaulieu Rails, as it ran along the fence marking the western boundary of the Beaulieu Estate.

It was the haunt of smugglers and working men from the shipyards on the Beaulieu River and William West’s ropeworks. Several non-conformist chapels and a church were built and in 1840 it acquired respectability as a separate parish named East Boldre.

Celebrating Somborne is available from the Somborne and District Society (01794 389688). For more on Hampshire, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel