WHEN the poet and hymn writer Isaac Watts penned the headline in 1715 he was living in considerable comfort in London, albeit surrounded by suffering.

But he must also have remembered the poor of Southampton, where he was born and educated at the Free Grammar School, writes Barry Shurlock.

More than a hundred years later the poor, sick and elderly were still evident throughout the country, though new measures were in hand. A new study has highlighted the value of existing records for local and family historians.

Speaking by Zoom to members of the Hampshire Archives Trust and the Local History Section of the Hampshire Field, Romsey historian Phoebe Merrick said: “It is easy to be smug about the treatment of paupers under the workhouse system of the nineteenth century – and certainly there was much in the theory and practice that was reprehensible.

“But it was a more equitable system than that which had preceded it, in that the cost of supporting the poor was spread onto a wider base than that of their immediate parish.

“As the century proceeded, the roughest edges of the system were ameliorated, with the employment of professional nurses to care for the sick. It is also apparent that by the last century, punishment and containment were gradually easing into what might be called a social work approach.”

“That said, the shame and humiliation of going into the workhouse remained with those affected and the abolition of the system in 1948 was seen as a great improvement by many.”

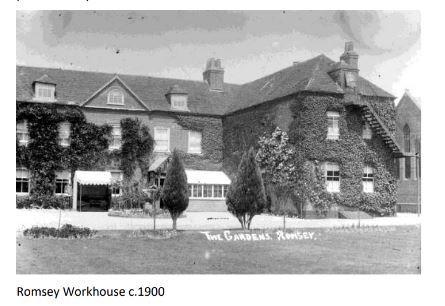

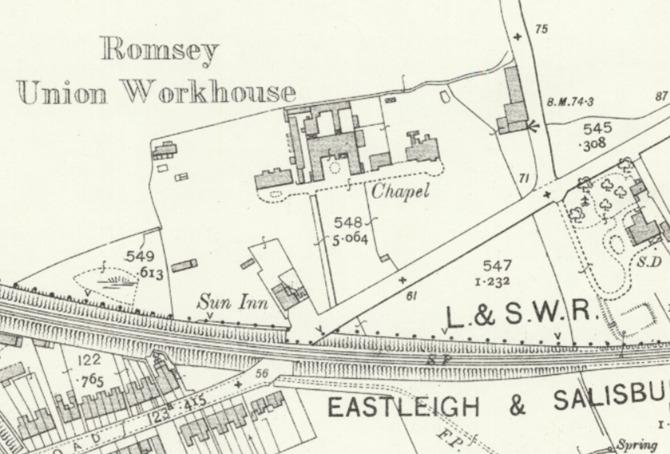

Her talk focused on the consequences of the New Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, especially in Romsey and surrounding parishes. Parishes were grouped into Unions, each with a single workhouse. The Romsey Union took over an existing building from Romsey Extra – the area outside the core of the town. It still stands as a place of shelter alongside the Winchester road, near the Sun Arch.

The Act wanted all able-bodied people to have ‘indoor relief’ inside the workhouse, where conditions were harsh. Although conditions in Romsey are not recorded, Phoebe said: “On the whole conditions, particularly in the early days, were dire. Those able to work were required to do so – for example in the laundry, in the kitchen or in the gardens surrounding the house, or making clothes for wear in the house.

“Many workhouse buildings were inadequately heated, and no provision for entertainment was made – no books, no toys for the children for example. Food was dreary, so its provision did not attract those who ‘should’ support themselves.”

“A balance had to be struck between allowing the poor to die of cold and starvation, or worse from communicable diseases brought on by their poverty on the one hand, and not keeping them in a degree of comfort that is perceived to encourage idleness on the other.”

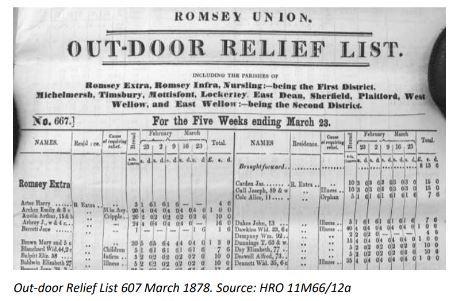

The Act also involved ‘outdoor relief’ (i.e. in the home), especially for the elderly and the ‘impotent poor’. In fact, outdoor relief in Romsey was much more prevalent than anticipated and vagrancy was rife. In 1890 for the half-year to March there were 601 people in the workhouse, as well as other families numbering 286 receiving outdoor relief and 480 vagrants.

Phoebe commented: “Of those receiving out-relief, the old formed the largest group. Also relieved were people with permanent disability such as deafness or being crippled. There were widows and abandoned wives with children to support. Many of these people were long-term recipients. Similar groupings are to be found in the workhouse itself.”

Workhouse records survive in the National Archives at Kew, which have been researched for Romsey by Colin Moretti. Others are in the Hampshire Record Office, particularly monthly printed lists headed ‘Out Door Relief’, which also show paupers in the workhouse or in an asylum elsewhere.

A model study of such records available online has been carried out for the City of York Union by the Clements Hall Local History Group.

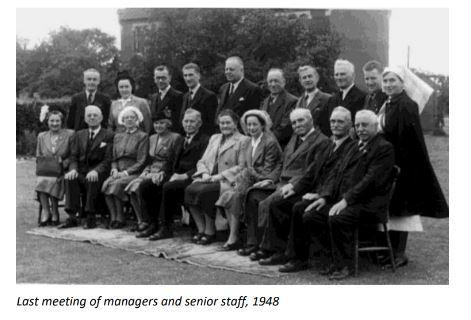

The Unions were run by a Board of Guardians with the support of a considerable staff – the Clerk, the Master and Matron of the Workhouse, an assistant matron, a chaplain, a medical officer, a porter, a cook, a barber, and a nurse. Reducing the cost of relief was always a major aim, and was largely dependent on the cost of bread, which between 1858 and 1880 varied for the usual 4 lb loaf between 3¾d and 6½d depending on the year and the parish.

Conditions of employment were less than ideal: “An example of how the [Romsey] Guardians treated their employees is shown by the way in which they dealt with the porter. In 1851, he had been absent for 3 or 4 weeks due to illness and because his absence was not causing problems with 14 vagrants it was decided to dispense with the post for the summer and the man was given a fortnight’s notice. By contrast the workhouse master who had been pestering the schoolmistress was allowed to resign.”

Individual Unions only wanted to help local people, which often sparked drawn-out arguments between, for example, Romsey Infra (the town centre) and Romsey Extra. “Settlement was based on birth, apprenticeship, payment or in the case of women, marriage but not widowhood, but people’s lives are messy and liability could lead to considerable disputes and a body of case-law – before 1834 between parishes and afterwards between Unions.”

There were many who had high hopes of the 1834 Act, according to Phoebe, as expressed in the 1850s by Mr Joseph May, Chairman of the Romsey Board of Guardians: “Formerly it was only under the protection of the Police that Guardians could attend their duties free from violence. Since then, striving to destroy the innate principle of pauperism, the amount given as relief was at least 50% less, and: ‘Were the poor worse off?’ On the contrary, with the exception of isolated cases, the poor were happier, because dependent on their own exertions.”

It is an argument that goes on. To find the talk, search YouTube with ‘Phoebe Merrick’. For more on Hampshire, visit: ww.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel