ON THE outskirts of Winchester are boreholes that go 70 ft into the chalk and were used more than 100 years ago in experiments reckoned to be ahead of their time in studies of climate change.

They were engineered by Lt-Colonel Henry Sollers Gunning Sparks Knight in the garden of his newly-built house in Harestock Road, near Winchester, to measure temperatures at various depths in the chalk.

As expected, at shallow depths the temperature was strongly influenced by seasonal weather at the surface, but at greater depths the effects were less. At three metres the temperature varied between 10 and 12℃, at nine metres between 9.6 and 10.2 ℃, whilst at 20 metres it remained constant at 10℃.

The findings will be familiar to anyone with a cellar. Outside it may be a heatwave or a frost, but in the cellar the temperature will be relatively stable – ideal for storing wine and cheese. Deep caves have the same properties, long appreciated by prehistoric peoples avoiding extremes of weather.

After retirement from the Army in 1876 Knight took up science and built a house, which still stands. Called ‘The Observatory’ it was named after the astronomical dome and telescope which he built in the garden. He was clearly a wealthy man and much more than a ‘blood and guts’ soldier. He was soon elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and later in 1881 joined the Royal Meteorological Society.

Knight ‘s boreholes (now probably built over) were lined with wood and provided with various means of ensuring the accuracy of the measurements. In the late 1890s Symon’s Monthly Meteorological Magazine commented: “We believe that the problems of earth temperature have never been attacked with the same amount of thoughtful care and elaborate instruments as Col. Knight has devoted to them.”

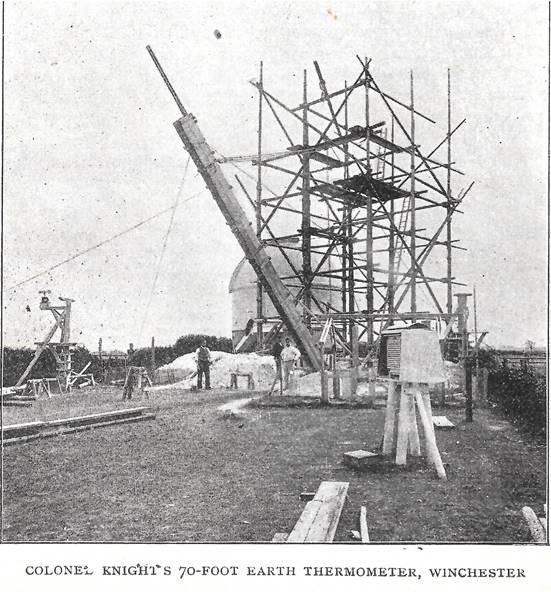

The story of his ‘earth thermometer’ was covered in the first issue of the Harmsworth Magazine of 1898, recently located on the net by local historian Mike Pettigrew. It published a photograph of the structure in the garden, commenting: “The scaffolding in the foreground was erected for the purpose of lowering an earth thermometer into the ground. This instrument, which is constructed to register the temperature seventy feet below the surface, is contained in the wooden chamber standing at an angle to the scaffolding, and was photographed during the sinking process.”

Reviewing Knight’s temperature measurements in modern times, meteorologist Philip Eden in his 2005 book Change in the Weather depicts him as a pioneer in the study of climate change: “These nineteenth-century experiments suggest a twenty-first century experiment for those who are not convinced that our climate is getting warmer.”

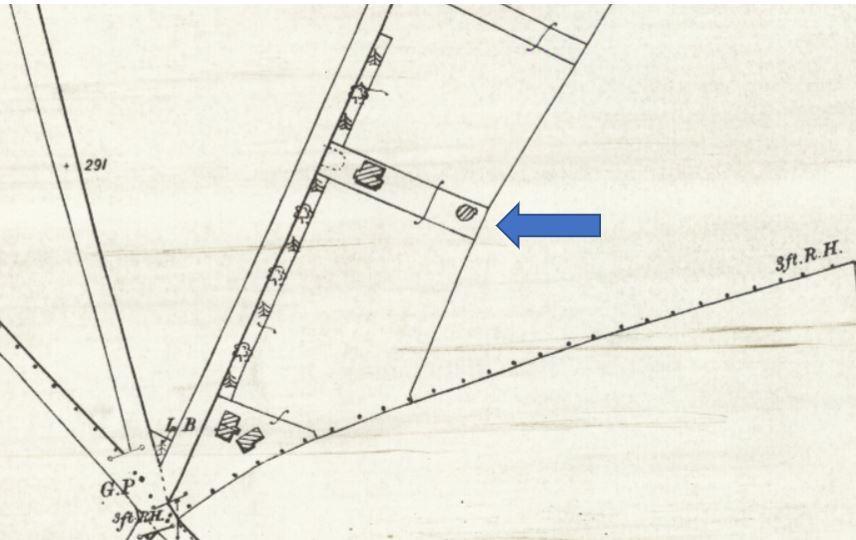

The astronomical observatory in the garden appears on the map in 1894 (but not 1908) and was obviously a prominent local sight. In the early 1900s the writer C.G. Harper walking up the Stockbridge Road referred to “the white-topped equatorial [a telescope mount that turns with the Earth] of an observatory serves to emphasise a wholly unobstructed view over miles of sky.”

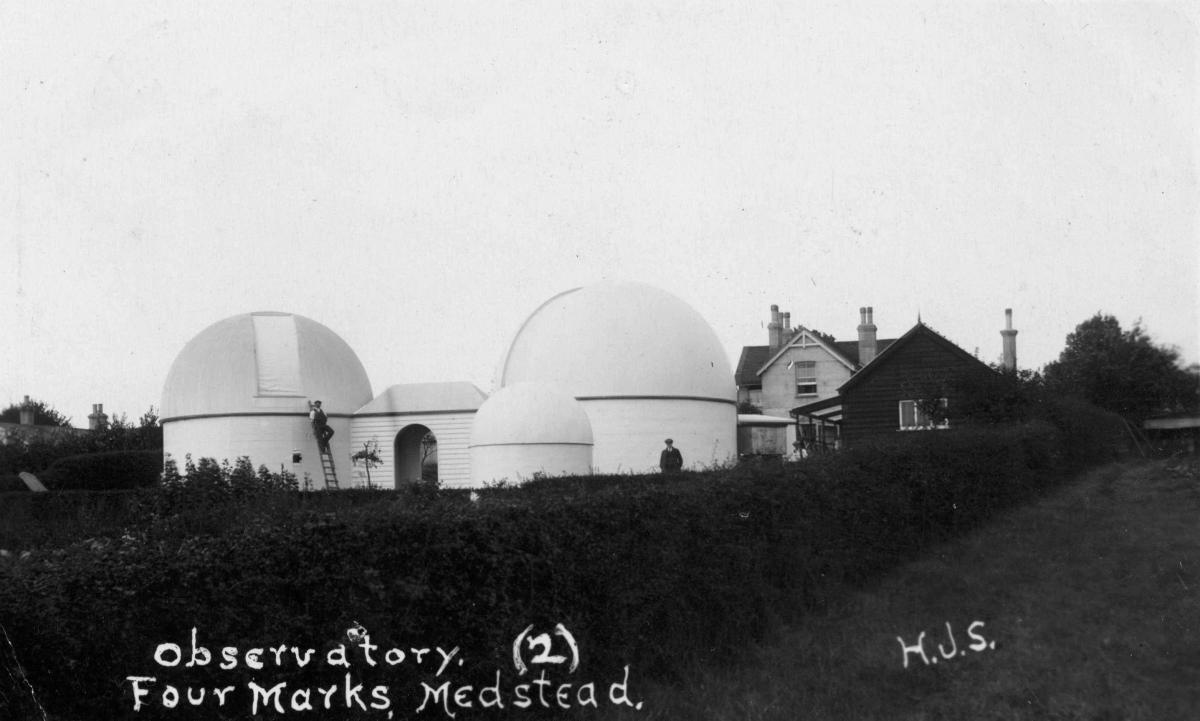

It was probably similar to, but larger, than the Alexander Observatory that stands today on Queens Avenue, Aldershot Military Town. Knight’s observatory is not listed in the Survey of Astronomical History, but others in the county are recorded at Four Marks, Romsey, Southampton, Portsmouth and Boscombe.

Knight was born in South Africa and lost his father – who held a commission in the Cape Mounted Riflemen – at the age of four. He came to England as a teenager and had a commission bought for him as an Ensign in the British Army, which he served for 31 years, including a spell with the 67th Regiment of Foot (The South Hampshires). At the end of his career with the rank of Brevet Major he commanded the 19th Regiment of Foot. In 1876 at the age of 47 he retired with the rank of Honorary Lt-Colonel to live in Winchester on full pay.

Knight’s family was probably relatively wealthy. His grandmother and two of her brothers had inherited an estate in the Caribbean belonging to a distinguished Irish naval officer, Admiral Richard Tyrell. In about 1853, as a young officer serving with the South Hampshires, Knight was quartered on the island ‘within a few miles of the Tyrrell property’, according to a History of the Island of Antigua by V.L. Oliver, published in the 1890s.

Although Knight married and had a family of two, his personal life was not straightforward. Whilst he retired to Winchester his wife, Elizabeth Jane, lived in Devon and Gloucestershire and described herself in census records as ‘a widow’. Even so, his military gravestone stands in the churchyard at Elmore, near Quedgeley, where she came to live with one of her daughters.

The Hampshire Chronicle noted his death in October 1904: “The deceased gentleman took a deep interest in the study of astronomy, the velocity of winds and various other meteorological phenomena. His observations and readings of storms, which have been published in our columns, have been read with great interest. ...[He lived] a quiet and secluded life, [and] devoted practically the whole of his time to the study of astronomy and meteorological phenomena”.

Littleton resident Brian Middleton, who has researched the subject with the help of astronomer Martin Lunn, said: “Knight must have had considerable means – that observatory would have cost between say £600,000-£800,000 in today’s money and maybe more depending on the telescope within.

“If you look at the gear he had the [total] capital expenditure must have been considerable, plus regular recalibrations of the meteorological equipment at Kew. The photo shows a Stephenson Screen on the right, an anemometer on the left and centrally, workmen installing a large ‘earth’ thermometer but of special interest is the observatory building at the back.”

For more on Hampshire, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here