AFTER the First World War the country was faced with rebuilding society in hopes of a brighter future. The Twenties brought brittle enjoyment and the Thirties despair. But those who could look back to the Edwardian age must have wondered how life could have changed so much, writes Barry Shurlock.

Of course, there were eventually some winners before the next war took its toll, and life for many did get better. But at the time the contrast between, say, 1913 and the immediate post-war period was stark.

In towns and cities in England the fruits of post-Reform Victorian benevolence had created a system of support that would morph into the Welfare State. And the sheer range of employment opportunities meant that young men and women flocked into urban centres to share the action.

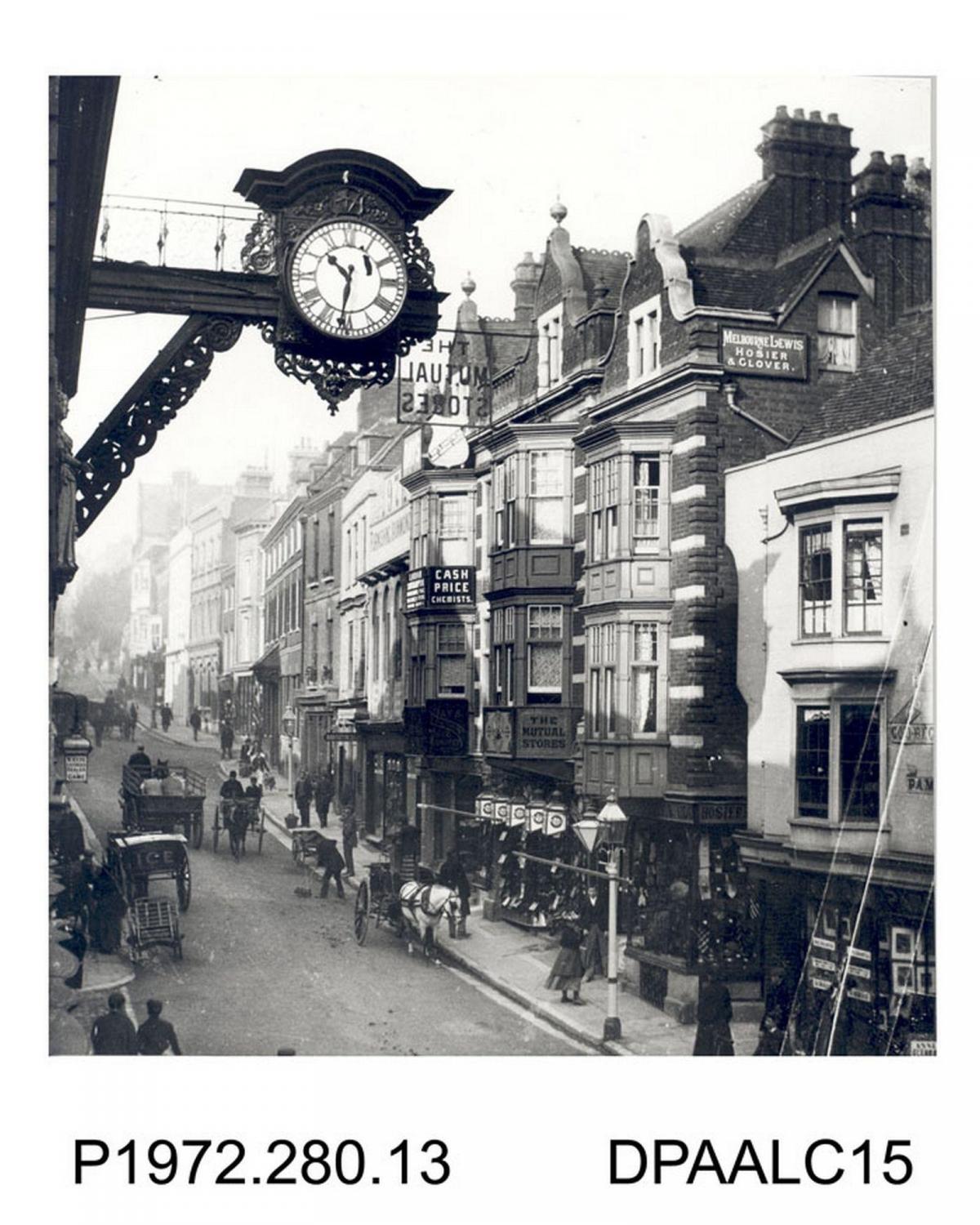

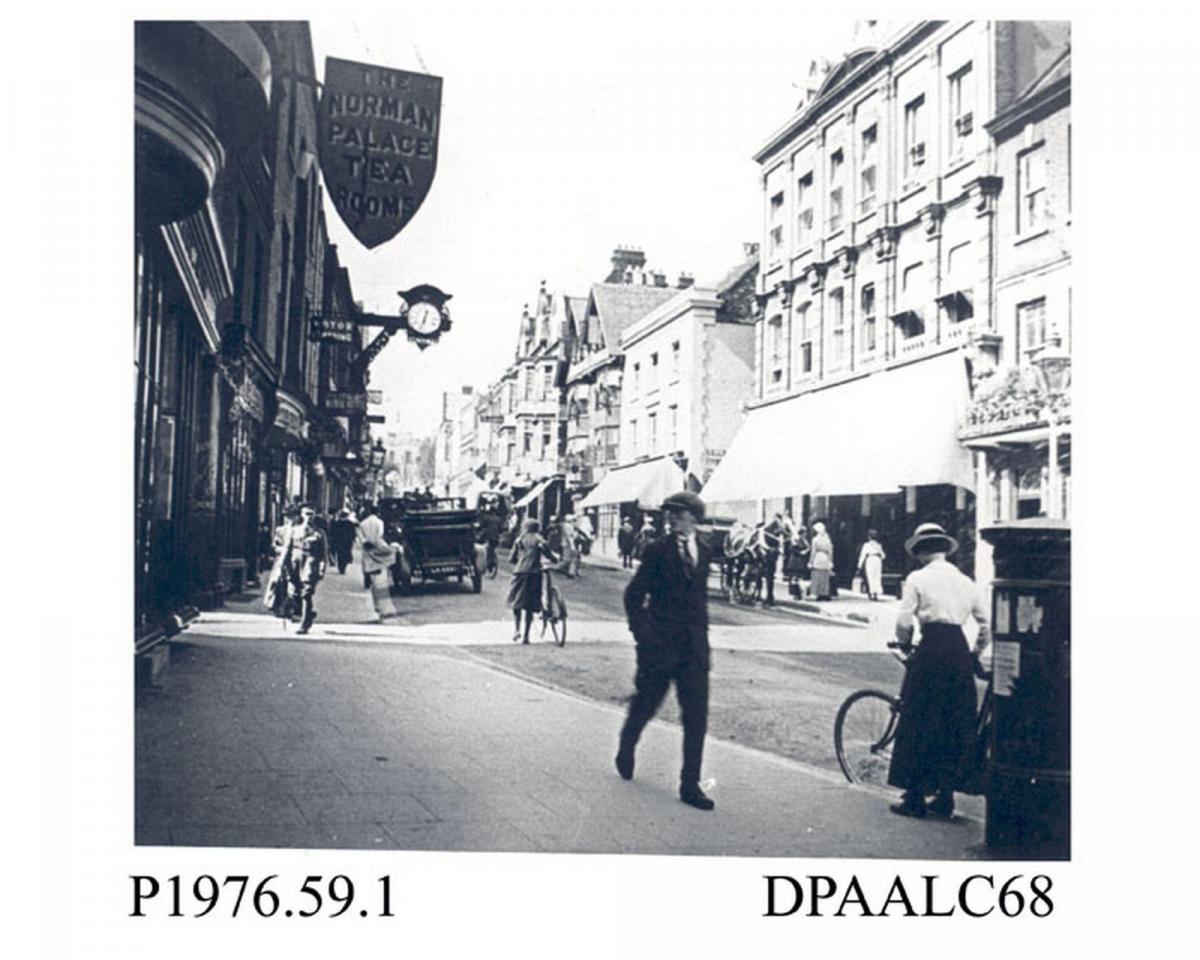

Places like Winchester, in particular, had blossomed in the second half of the 19th century, propelled by growing prosperity in general and the advent of the railway. Between 1801 and 1851 the population doubled and by 1911 it had virtually doubled again to, 23,380, to be exact.

The suburbs of St Cross, Fulflood, Hyde and others mushroomed. And yet almost all horse power was still of the animal kind and transport facilities meant that “countryisation” – let alone globalisation – was a long way in the future.

As a result, urban centres offered an extraordinary range of local pursuits, especially for young men. Today, any particular service might be centred in one place, yet serve the whole of southern England or more. But then each town had its own local services and required local people who could learn the necessary skills.

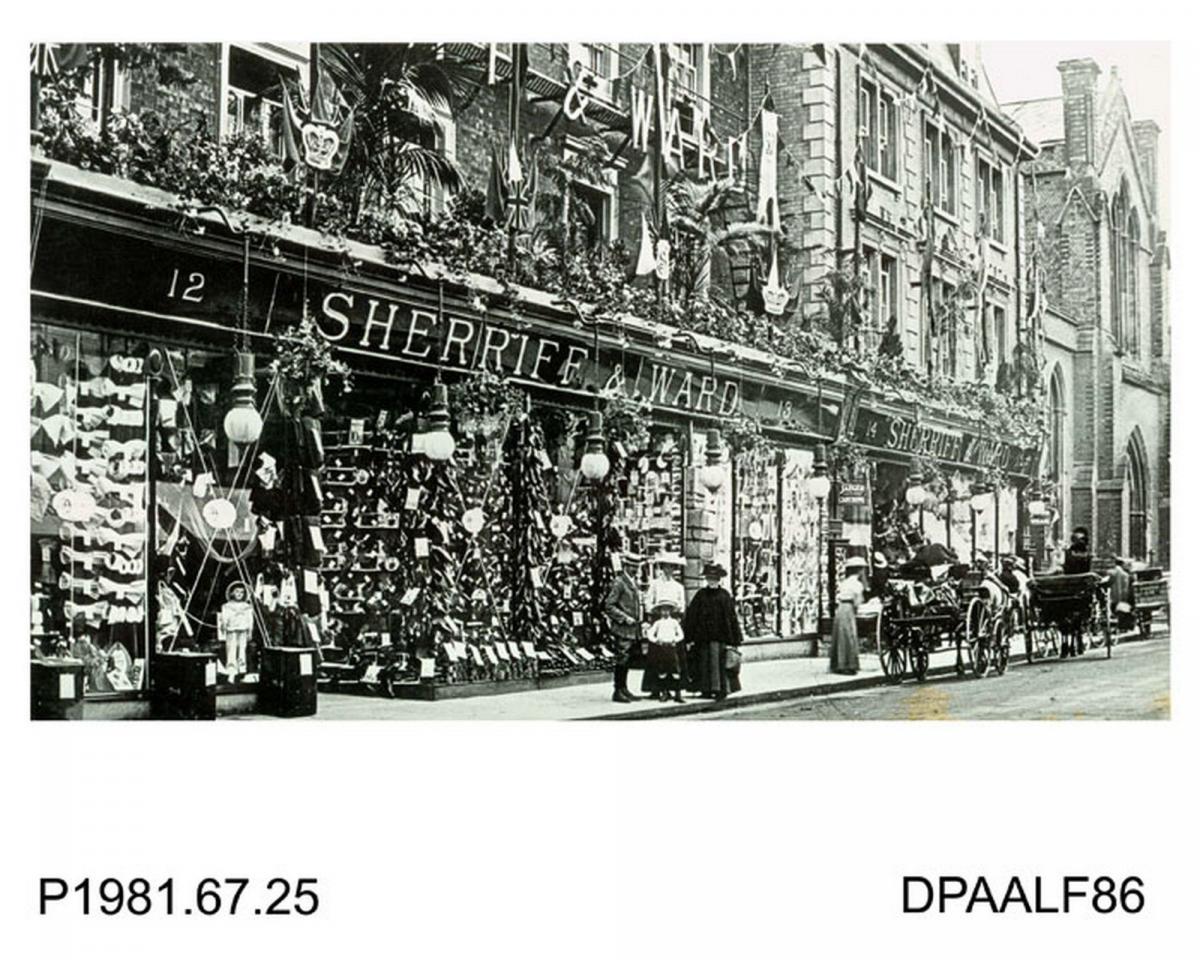

Directories of the day– available in the Hampshire Record Office or online from the University of Leicester – tell the story in great detail. What is most striking is the huge range of occupations and activities carried out in a place like Winchester. In 1913, for example, just a list of them takes up three pages in a directory published by local printers Warren & Son.

In addition to a large number of High Street retailers and everyday trades there is an exotic range of specialists, including artificial fly dressers, brass finishers, badge makers, beehive makers, currier and leather sellers, cricket bat makers, ice merchants, firework makers, engravers, tinsmiths and many, many more.

It is difficult to think of an occupation in this cathedral city that is not listed. There are stonemasons, surgical instrument makers, lime burners, lithographers, dyers, corset makers, horse dealers, carvers and gilders, and so on.

In short, for people of all abilities there was a good chance that they could learn some trade or skill and find a job. Of course, a provincial centre generally had to bow to greater skills in London and other large centres, and the more ambitious might chose to train there and bring their skills back to Hampshire.

Then there was the bewildering array of agencies and offices of various kinds. Unsurprisingly for a cathedral city there were many societies with religious aims. These included the self-explanatory Diocesan Mission for the Deaf and Dumb, the Church Missionary Society and the Diocesan Mission Studentship Association.

Also Winchester had a branch of the Zenana Bible and Medical Mission, which sought to increase the number of female doctors in the Indian subcontinent, both by recruiting British doctors and “encouraging Indian women to study medicine in their pursuit of conversion”. It took its name from that part of the house reserved for women in India, the zenana.

Many other organisations supported women in a variety of ways. There was a branch of the National Union of Women Workers, a Girls Friendly Society, and the Winchester Society for Visiting Nurses. “Fallen girls” were catered for, amongst others, by the Winchester Refuge, the North Walls Home and the Ladies’ Association for the Care of Friendless Girls.

Professionals and military men facing hard times were supported by other charitable bodies. These included the Church Schoolmasters’ and Schoolmistresses’ Benevolent Institution, the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Help Society, the Rifleman’s Aid Society the Incorporated Clergy Sustenation Fund, to name a few.

This is merely a taste of everything that was going on in Winchester in 1913. As well as municipal authorities such as the city council, the police, the prison and hospital, there were the School of Art, the Diocesan Training College (the roots of the University) and the Law Courts, together with other worthy bodies, such as temperance missions and friendly societies – the Shepherds, the Foresters, the Hearts of Oak and suchlike.

No doubt some of these institutions used voluntary labour, but there were many others that on the eve of the First World War offered opportunities for a wide range of talents and personalities. As the 20th century wore on, all this was progressively “delocalised” by the internal combustion engine, the telephone and, of course, the computer. In a post-furlough world, videoconferencing and online shopping are now set to throw the dice in the air once more.

For more information on Hampshire history, visit: www.hampshirearchivestrust.co.uk.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here