AS an eminent barrister, Winchester QC Roger Backhouse fought bravely for his clients, winning a string of high profile cases and appeals.

So when he faced a life-threatening battle with antibiotic-resistant superbugs and necrotising fasciitis, a flesh-eating infection in his foot, after a holiday in India, Mr Backhouse, 78, agreed to an unconventional cure – a new super-charged honey.

Today, as he recovers at home, the bacteria-killing honey, he says, undoubtedly helped save his limb and possibly his life.

“Amputation was a very real probability, rather than just a possibility,” he says. “I would undoubtedly use the word magical to describe Surgihoney as it undoubtedly saved my foot. It felt to me as if it was working from the moment it was applied.”

The honey-based product is a world first. It is medical grade honey that has been engineered to enhance its antimicrobial potency. Its clinical use was pioneered at Winchester’s Royal Hampshire County Hospital and is now available on prescription on the NHS.

Researchers believe it could transform our ability to fight infections at a time of growing resistance across the world to antibiotics.

Scientists from the National Institute for Health Research and Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre – the research arm of the NHS – have proven that under laboratory conditions the bioengineered honey can wipe out colonies of bacteria, or biofilms, found in non-healing wounds, including MRSA and E.coli.

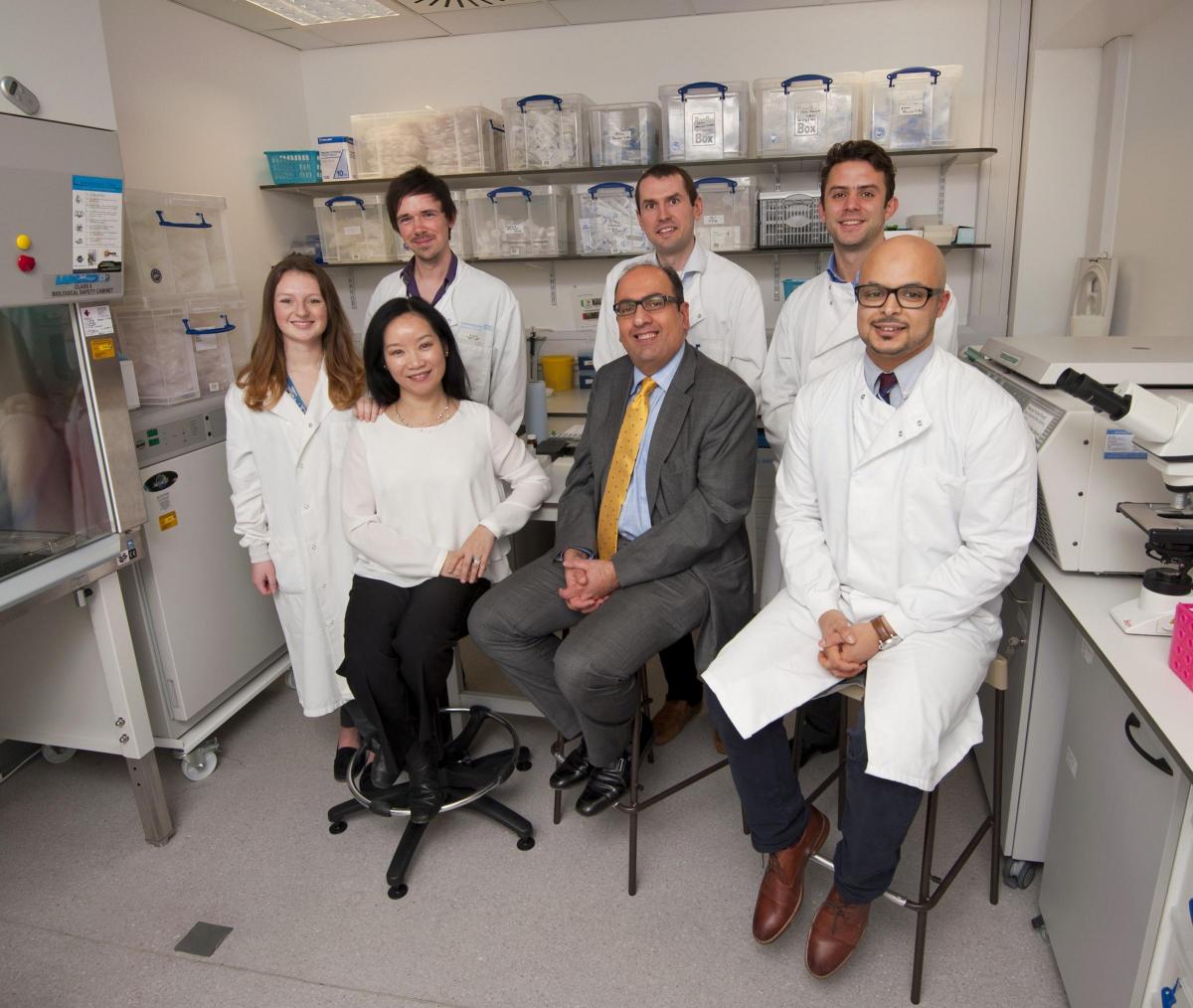

Now leading scientists and surgeons at the University of Southampton are investigating its potential as novel therapy for patients with chronic sinus infections.

Mr Rami Salib, Associate Professor of Rhinology and Consultant Ear, Nose and Throat Surgeon, who heads the Upper Airway Research Group, said: “Surgihoney sparked my interest because I felt I could take this concept and apply it to my field for treating chronic nose and sinus infections. The problem of chronic sinus infections not only impacts significantly on patients’ quality of life but these infections tend to be resistant to antibiotics and patients often end up needing multiple operations and a lot of antibiotics during their lifetimes.” Mr Backhouse’s ordeal began after he flew out for a five-week tour of India and Kashmir on September last year.

After enjoying Varanasi, the spiritual capital of India, where pilgrims bathe in the river Ganges, he set sail on a houseboat for five days, before planning to fly to Kashmir.

“I don’t quite know what happened to me on the boat but I woke up in the night violently ill and during that time I also noticed damage on the top of my right foot,” he said. “It swelled up and I was so ill and weak that I had to be helped off and I was pushed around in a wheelchair.

“When I arrived in Kashmir, I became even more sick so I ended up spending three days in a hospital and the doctors were first rate. I was placed on a drip to rehydrate me and I was given medication so I discharged myself, deciding that if I was going to have to lie down, I would rather do that on a house boat.”

On the plane home, Mr Backhouse’s foot quickly became far worse and started “oozing blood.” Mr Backhouse, a QC for 18 years, who retired in 2002, said: It became clear that I needed to go straight from Heathrow Airport to Winchester hospital and placed under the care of consultant Matthew Dryden – by luck a pioneer of the use of Surgihoney.”

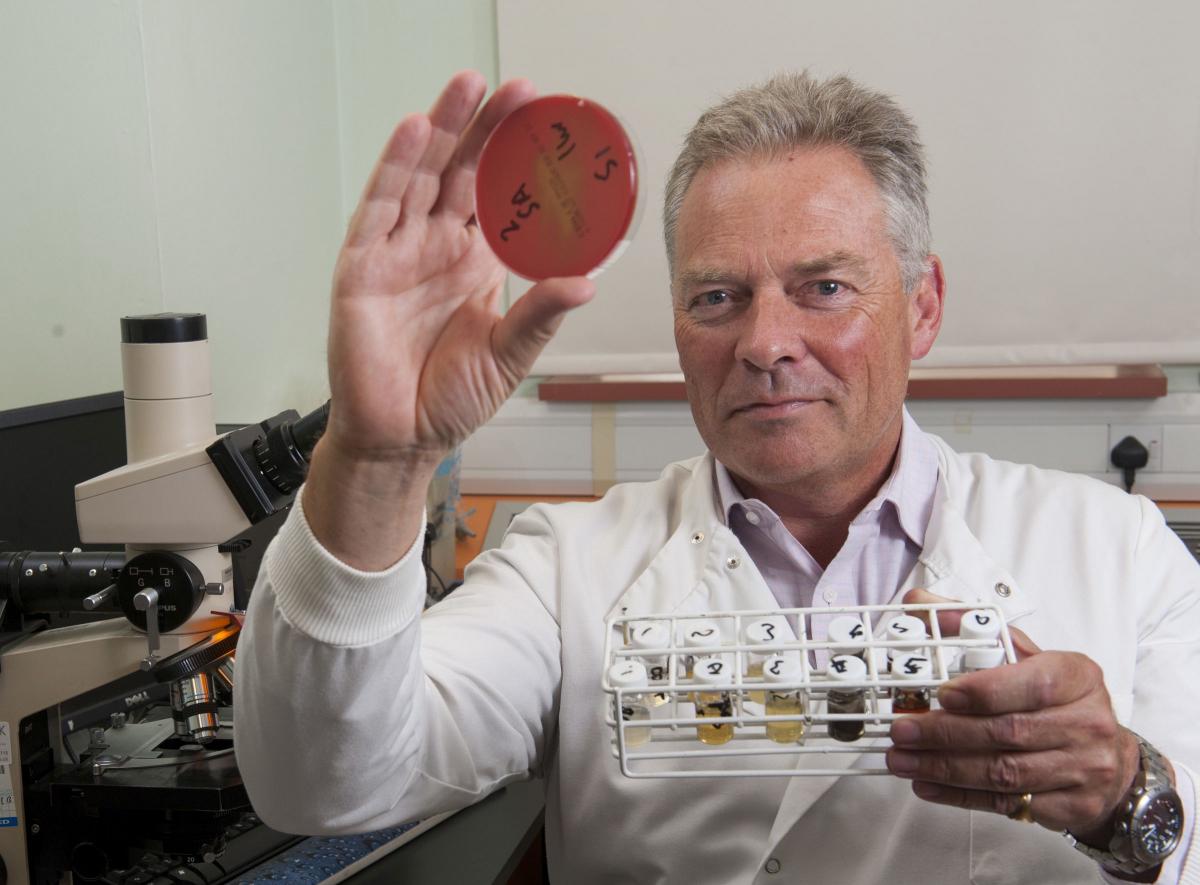

Dr Dryden, consultant microbiologist and infection specialist at Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Public Health England, diagnosed necrotising fasciitis and two superbugs acquired while in hospital in India, including a multi-drug resistant strain of E.coli.

The strain, called NDM-1-E.coli, is so dangerous it is resistant to the most powerful antibiotics. The other superbug was CPE Enterobacter.

Mr Backhouse, who was kept in isolation, needed immediate and limb-saving surgery. “Because there was so much tissue damage due to the necrotising fasciitis, they debrided my foot, cutting away the dead tissue and infection,” said Mr Backhouse.

While intravenous antibiotics drips were able to control the necrotising fasiitiis, the Surgihoney applied every three days over a two-week period, wiped out both superbugs.

“It was a very big wound covering more than half of the upper part of my right foot and most of the outside of my right ankle. It was an ugly sight and very painful.

After seven days, swabs showed complete eradication of the multi-drug resistant bacteria which could have caused a major infection control risk to the hospital. Mr Backhouse was then able to have skin grafts at Salisbury hospital.

Commenting on the case, Dr Dryden said: “Roger was admitted to hospital in India. I suspect it was here that he acquired NDM-1 E.coli and CPE Enterobacter. These are highly and almost pan resistant microbes which can spread easily like MRSA in health care environments and for which we have so few treatment choices.”

He added: “Without Surgihoney clearing the resistant germs the patient may have had a secondary infection due to these bugs and possible further surgery, or they would have spread to the hospital environment and other patients.

“These bugs are really hard to clear. It is the end of the line for antibiotics if patients get deep infections. So it is really exciting that Surgihoney has been so effective in clearing these.”

Breakout box Honey has been used for millennia to clean wounds and burns..

But there is a huge variation in the antibacterial potency of honeys depending on the floral source. This lack of standardisation has been a major stumbling block to its use in modern medicine. Until know, the most potent natural honey was generally as Manuka but it depends for its potency on pollen from a particular tree in New Zealand, limiting supply.

Surgihoney is different because scientists have invented a way to precisely control the antimicrobial potency of different honeys. Ultimately, this discovery means it can be produced from honey from any floral source and in different and reproducible strengths.

Its secret weapon is the ability to deliver low doses of hydrogen peroxide as to the infection site for a prolonged period rather than a large amount at the time of dressing. It kills bacteria but leaves human cells intact.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here