FOR more than 2,000 years she lay hidden beneath mounds of volcano ash that killed thousands.

Since being unearthed three years ago the ancient warrior’s face – shattered in the same eruption that buried Pompeii in AD 79 – has remained a mystery to archaeologists.

Now scientists in Southampton are making a groundbreaking bid to restore the Roman statue to her former glory.

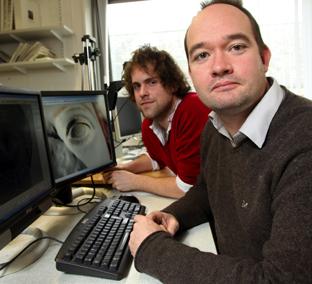

The team has begun piecing her face back together by using the same technology used to create films such as WALL-E and Ratatouille.

Thought to represent a wounded warrior princess, the statue, discovered in the coastal town of Herculaneum, is remarkably preserved with her painted hair and eyes as vivid as the day Mount Vesuvius erupted.

She will have her nose and mouth – both lost in the rubble – digitally recreated by studying other surviving statues.

While the original statue will remain untouched, scientists want to place its digital recreation in a virtual museum complete with an opulent Roman residence.

Archaeological computing expert Dr Graeme Earl, of the University of Southampton, said: “What makes this statue so special is that the paint is preserved after 2,000 years.

“When you normally think of a Roman statue it is always white marble, but the standard of decoration on this statue is extremely high, right down to the eyes and the hair.

“Over the coming year we will be working with experts in Roman sculpture and painting from around the world in order to produce the most accurate simulations possible.

“We can also put it in a context by reconstructing a building where it was likely to have been and put the statue back in its location.”

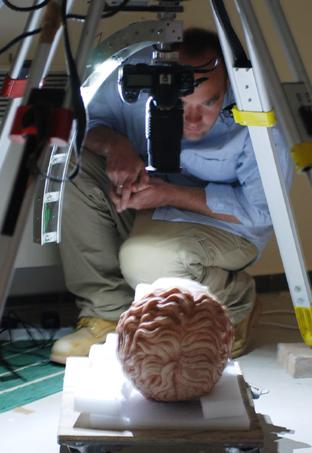

A team from the University of Warwick visited Italy to measure every surface of the head to within 0.05 of a millimetre to create a physical 3-D model of the head.

Dr Earl also used a novel form of photography to provide a detailed record of the texture and colour of the painted surfaces.

Archaeologists are still hopeful of unearthing the warrior’s missing body in the future, while her digital creation will be completed by the end of the year.

“Cutting-edge techniques are vital to the recording of cultural heritage material, since so much remains unstudied or too fragile to analyse,” Dr Earl added.

“Our work at Southampton attempts to bridge the gap between computing and archaeology.

“It also allows us to create models of how past objects and places may have appeared, and even how they felt and sounded.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel