Scrooge’s astonishing offer to Bob Cratchit: ‘I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your family’, may be fiction, but is echoed by some real-life events, writes Barry Shurlock

CHRISTMAS has changed dramatically over the years. Many families travel huge distances to get together, or failing that link up on Zoom. Many presents are bought online. On the other hand, few will roast chestnuts on an open fire and fewer still – if any! – will visit friends and neighbours on horseback.

For most people ‘Christmas’ now extends over a week, and into the New Year, whereas once – with the exception of the industrial North – an extra day or two was all that most people could expect. And those who were ‘in service’ had no break at all.

Despite these changes, that effervescent thing called ‘the Christmas spirit’ endures. It may not always have been easy to sustain in a world bedeviled with problems, but is often in evidence.

The classic expression of it in fiction is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, published in 1843 by Chapman and Hall (an imprint still extant) with illustrations by the caricaturist John Leech. The story of Scrooge’s change of heart is a powerful statement of secular morality. It was beautifully portrayed in a recent production of the tale by Winchester’s Chesil Theatre.

In 1907 a special edition of the book was published to raise funds for the Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Treloar (1843-1923), who contributed an introduction. He was an entertaining speaker, a clubman and self-publicist – but above all he exercised formidable philanthropy in Hampshire.

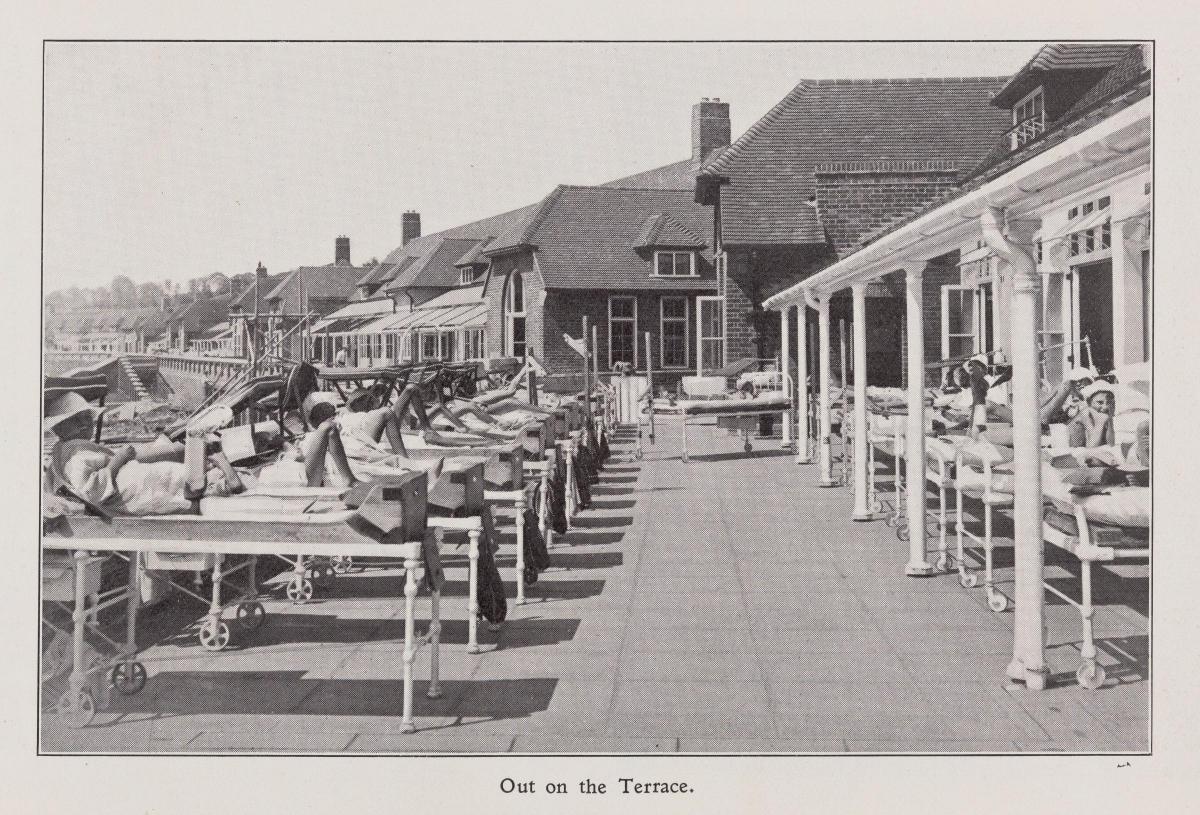

He made a fortune manufacturing carpets and set his heart on helping young people with disabilities, especially those with bone disease due to TB. His Little Cripples’ Fund amassed £60,000, which was enough to buy and equip a former military hospital at Chawton. It opened in 1908 as the Lord Mayor Treloar Cripples’ Hospital and College.

The full story is told in Treloars: One Hundred Years of Education, published by local historian Jane Hurst, who taught at school for 25 years. In Spring 1907 Sir William became aware of a site at Chawton– where the school was located until 1932 – and formed a Trust. An Act of Parliament was then passed to take over the premises from the Military.

In 1948 it became part of the NHS. The Treloar School and College at Holybourne, Alton, continues, still in the hands of the trust, offering ‘outstanding teaching, learning, professional care, therapy, advice and guidance’ to about 170 students aged 4-25 years (texting TRELOARS to 70085 gifts £10).

Christmas has always been a time for employers to ‘reward’ their staff. Some of them were very grateful for a practice that to modern eyes looks like condescension! In 1796, farm labourer John Elton even wrote verses in thanks for ‘food and raiment’ given by Lady Malmesbury, wife of James Harris, Earl of Malmesbury.

Estate workers at Southwick in the south of the county were also rewarded, with all details faithfully recorded in the ‘Christmas Beef Book’. A ledger in the Hampshire Record Office for the period 1892-1937 gives lists of employees and their children, with details of the meat, suet, flour and plums given to them at Christmas.

Most gifts were no doubt of ‘food and raiment’, but Southampton author Eleanor Culley Davidson had another idea. She bequeathed the copyright in her ‘tales’ on the condition that 'as long as the present edition lasts [the legatee] is to send every Christmas a dozen or more of all the stories to each of the Royal Hospitals of Haslar and Netley for the ‘sick soldiers’.

Other snapshots of Christmas abound in the archives. In the run-up to festivities in 1746, Ben Light from Baddesley wrote to his boss, the landowner John Nicoll in London, asking him how much game he was to kill and send up to London.

Nicoll was a grandee with estates in Middlesex, who had inherited Baddelsey and lands elsewhere. At his death two years later the estate passed to his daughter Margaret, who subsequently married James Brydges 3rd Duke of Chandos, so forging a link with Avington.

In some households Christmas was an opportunity for theatricals. When Alfred Bowker, mayor of Winchester 1900-1901, invited his close friend Sir George Elliston MP and family, to enjoy the festivities at his grand house at Shawford, The Malms, they wrote and produced plays, some of which are recorded in the visitors’ book.

Alfred was a successful solicitor in Winchester as well as a lover of the arts. He played a major role in ensuring that the city became the site of the iconic stature of King Alfred by Hamo Thornycroft after its millenary celebrations in 1901. He was also a sculptor and painter in his own right and several of his works are still held by the Hampshire Cultural Trust.

Insights into Victorian Christmas are hidden in a long series of letters held in the HRO. These were between two spinsters, Anne, daughter of politician William Sturges-Bourne MP and Marianne, daughter of Jeremiah Dyson, Deputy Clerk of the House of Commons.

Sturges-Bourne was a Poor Law reformer and a close friend of Canning. He was notorious for declining offers of high office, including Chancellorship of the Exchequer. In 1822 he succeeded to a very large fortune that included Testwood House in the parish of Eling, where Anne spent her days.

The two women were passionate supporters of the Oxford Movement, centred around John Keble and Charlotte Yonge at Hursley. They were also both aspiring writers, penning moral tales to support their beliefs. There were gifts at Christmas for children at Sunday school, ‘some warm, some literary’. The scope of their reading was immense, and despite being kept out of politics they were on top of issues of the day.

Their letters on Christmas revolve around the weather and the company they kept. Anne’s father was often constrained by gout and her mother by various health problems – knees, head and eyes. Even so, a heavy cold was welcomed by Anne as an excuse for not accepting invitations to dinner and the like.

She did, however, manage to get to church at Eling, where the clergyman ‘did his worst as to blunders’ – whatever they were. She was also challenged by her maid, who questioned how sadness over the death of Christ during communion at Christmas could be reconciled with merriment at his birth.

Some Christmases went terribly wrong. In 1842 Marianne reported an accident when two young brothers who had spent the day with them left in their carriage, which was ‘run away and overturned as soon as they left the gate’.

One of the brothers had to be ‘doctored and put to bed’, though the other was more ‘interested in the moonlight’. The horse was ‘caught and brought back’. To allay suspicions, Marianne claimed that ‘overdrinking at the Rector’s’ was not the cause.

In 1857, Anne wrote to Marianne with a long account of Christmas at Testwood House. There were 60 guests, assembled around a tree in the library, lit with coloured lamps and Chinese lanterns, despite ‘fear of conflagration’. There was tea in the study and supper in the dining-room, with children having ‘high romps in the hall and staircase’.

Some things never change.

barryshurlock@gmail.com

CAPTIONS

Marley’s ghost, by John Leech

Scrooge’s third visitor, by John Leech

An early label for Treloar’s. Image: Wellcome Collection

Treloar’s, open air treatment on the terrace. Image: Wellcome Collection

The centenary history of Treloar’s

Testwood House, the home of the Sturges-Bourne family. Image: OS 1895

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here