THE earldom of Southampton lasted for just over a hundred years, from its first creation in 1537 until the line died out in 1667. The idea, however, of Southampton being the seat of an important earldom dates back much earlier and is linked to French Romances around the time of the Crusades.

The mythical knight Sir Bevis of Hampton was styled the son of ‘Guy, Erle of Southampton’, William Camden in his history refers to Bevis as a Saxon who tried to stem the Norman invasion, making a stand at the battle of Cardiff in Wales. Later versions of the tale show Bevis vanquishing the Italian merchant colony in London and he was a popular figure when antagonism to foreigner was at its height in 1456/7.

By the 15th century the town of Southampton, like other towns in England, was concerned with defining their physical space, creating symbols of civic government and raising the profile and influence of their towns. As well as developing political ceremony, patronage and regalia this included looking back into history to discover a suitable founder – a Saxon king or Saint, or other likely heroes. Southampton had a ready-made hero in the story of Bevis of Hamtun. The introduction of printed texts and illustrations made the story more accessible for readers and non-readers alike. Symbols taken from the stories such as lions, dragons and unicorns, were used to decorate the gates and civic buildings of Southampton. Sixteenth century oak panel paintings of Bevis and his squire Ascupart were hung on the Bargate, the main entry point to the town. They survived in this location till the 19th century, when they were moved inside the Bargate.

The text of Sir Bevis of Hamtun was also studied in schools as a template for knightly behaviour. King Henry V had tapestries illustrating the story, which he took with him on campaign to Agincourt. The tale was so well-known that the writer George Peele likened Henry Wriothesley, third earl of Southampton, to Bevis after his appearance at a court tournament in 1595. Everyone reading Peele, knew the knightly attributes and struggles that Bevis had overcome. Bevis had had his patrimony stolen from him, was sent into exile, suffered many travails before returning triumphant to reclaim his inheritance. In the charged political times of the late 16th century the parallels became even more significant.

When Henry VIII created the title of the Earl of Southampton it was to reward one of his ‘new men’, William Fitzwilliam, who served and survived as one of the king’s privy councillors. When Fitzwilliam died without issue in 1542 the title was dormant for a few years before the second creation in the person of another of Henry VIII’s non-aristocratic henchmen, Thomas Wriothesley. Wriothesley had previously served under Thomas Cromwell but survived his downfall and was eventually rewarded with his title at the close of Henry’s reign in 1547. He only enjoyed it for three years before his death in 1550. Thomas Wriothesley had been an enforcer of the Henrician Reformation and had benefited from the appropriation of church lands, particularly the abbey of Beaulieu and that of Titchfield. He was, however, like his royal master, quite conservative at heart. This along with the influence of his wife saw his son Henry, the second earl brought up as a Catholic.

The second earl coming to age during the reign of Elizabeth I was lucky to escape with his life from his plotting and spent periods locked up in the tower. In fact, his early death at the age of 36 in 1581, probably saved him from a worse fate. His marriage to Mary Browne, also a Catholic, had not been successful and the couple lived apart, and after Henry’s death, their son was brought up in the household of Elizabeth I’s chief advisor: Lord Burghley.

The third holder of the title was probably the most well-known. Also called Henry, he was as reckless as his father. He married in 1598, without the consent of the Queen, to Elizabeth Vernon and then made the situation worse by throwing in his lot with the ill-fated Earl of Essex. Both men had been favourites of the ageing queen, but were impatient for power, and Essex particularly believed he could succeed the childless Elizabeth I. The rebellion came to nothing and Essex was beheaded in 1601. The Earl of Southampton’s property was seized including his house in Southampton known as Bull Hall. Householders were expected to attend the local Court Leet, held on Southampton Common, but the surviving records recorded Elizabeth I’s failure to attend. Many thought the Earl of Southampton would suffer the same fate as Lord Essex, but instead he merely languished in the tower until released by James I.

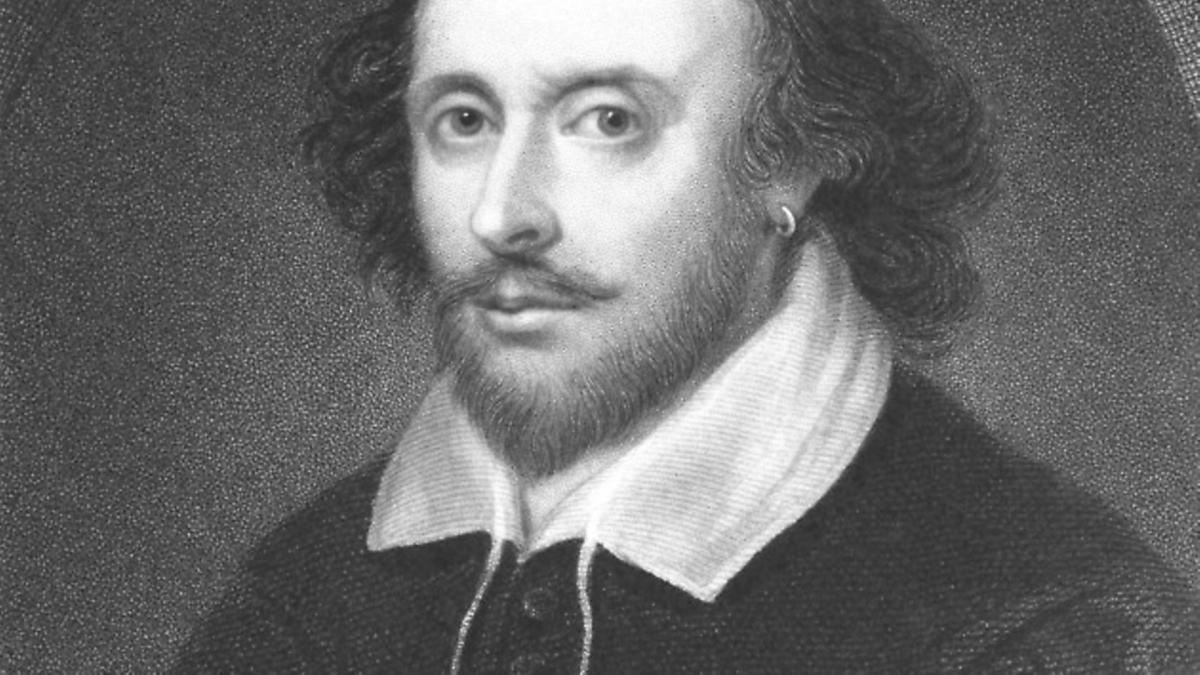

Once released from captivity the third earl turned his attention to the development of colonies in the new world particularly the development of the area known as Virginia and the first successful colony at James Town. This promotion also helped the port of Southampton which became a key port for early migrants to the New World, including the Mayflower pilgrims. The third earl’s other claim to fame was his patronage of William Shakespeare, who dedicated works to him including, Venice & Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Shakespeare was also familiar with the stories of Bevis of Hamtun and referenced Bevis in King Lear and took themes from his tales which he used in Hamlet. He was also inspired by stories of early colonists’ voyages to America, including that of Stephen Hopkins of Hursley and Upper Clayford, whose ship Sea Venture was wrecked off Bermuda in 1609. That story inspired The Tempest. It is likely that Shakespeare visited the town of Southampton in 1593/4 as part of a joint tour being made by the Admirals & Chamberlains men, whose licence to perform is recorded in town records. Shakespeare was also aware enough of the town’s history to include a pivotal scene in his play Henry V about the Southampton Plot. Local oral history also claims that Romeo & Juliet was premiered at the earl of Southampton’s private playhouse at Titchfield.

As for the earls’ links with the town whose title they bore, this is usually illustrated by the exchange of gifts. To the earls, the traditional present of wine but also more exotic fair such as marmalade, sugar, lemons and oranges was given. In return the mayors of Southampton would receive a gift of bucks from the earl’s estate and even on one occasion enjoying a hunting trip the second earl laid on at Titchfield. The town would look to the earls to use their influence at court on the town’s behalf. This patronage however was to be relatively short-lived. The third earl and his eldest son perished whilst on campaign in the Low Countries in 1624. The third earl’s surviving son, Thomas, succeeded to the title but when he died without a male heir the title died with him.

Southampton was briefly raised to a Dukedom in the reign of Charles II, who bestowed it on Charles Fitzroy one of his many illegitimate children. It was passed to his son William, but he also died without issue so the title became extinct in 1774.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here