By John Pilkington

YOU couldn’t make this story up.

In 1868 Queen Victoria’s government mounted an extraordinary bid to rescue a clutch of European hostages deep in the Ethiopian highlands. They built a Red Sea port and a railway across the coastal plain, then sent 13,000 British and Indian soldiers together with 44 Indian elephants to carry their heavy guns into the heart of Africa.

A hundred and fifty years later I’ve been following their route, partly on foot with a donkey, and have been comparing Eritrea and Ethiopia then and now. I found people who are boisterous and charming, living in a dramatic and extremely challenging land. It was history and adventure combined!

Starting on the Red Sea, I spent last December tracing the expedition’s route up to Eritrea’s high country. Unfortunately Eritrea has a terrible human rights record, and water and electricity are a real luxury, so I was surprised and delighted to find that despite these very serious problems its people manage to laugh and smile a lot.

When the Italians came to rule Eritrea 130 years ago, they were so taken by the perfect mountain climate of its capital, Asmara, that Mussolini set about transforming it into the Art Deco hub of his pipedream East African empire.

Confronted by the closed and guarded border with Ethiopia, I took a roundabout route to the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, then made my way slowly back to the border to rejoin the track taken by the Victorian expedition. By a stroke of luck I reached the city of Gonder in time for Epiphany. Local people call this Timkat, and go quite mad about it.

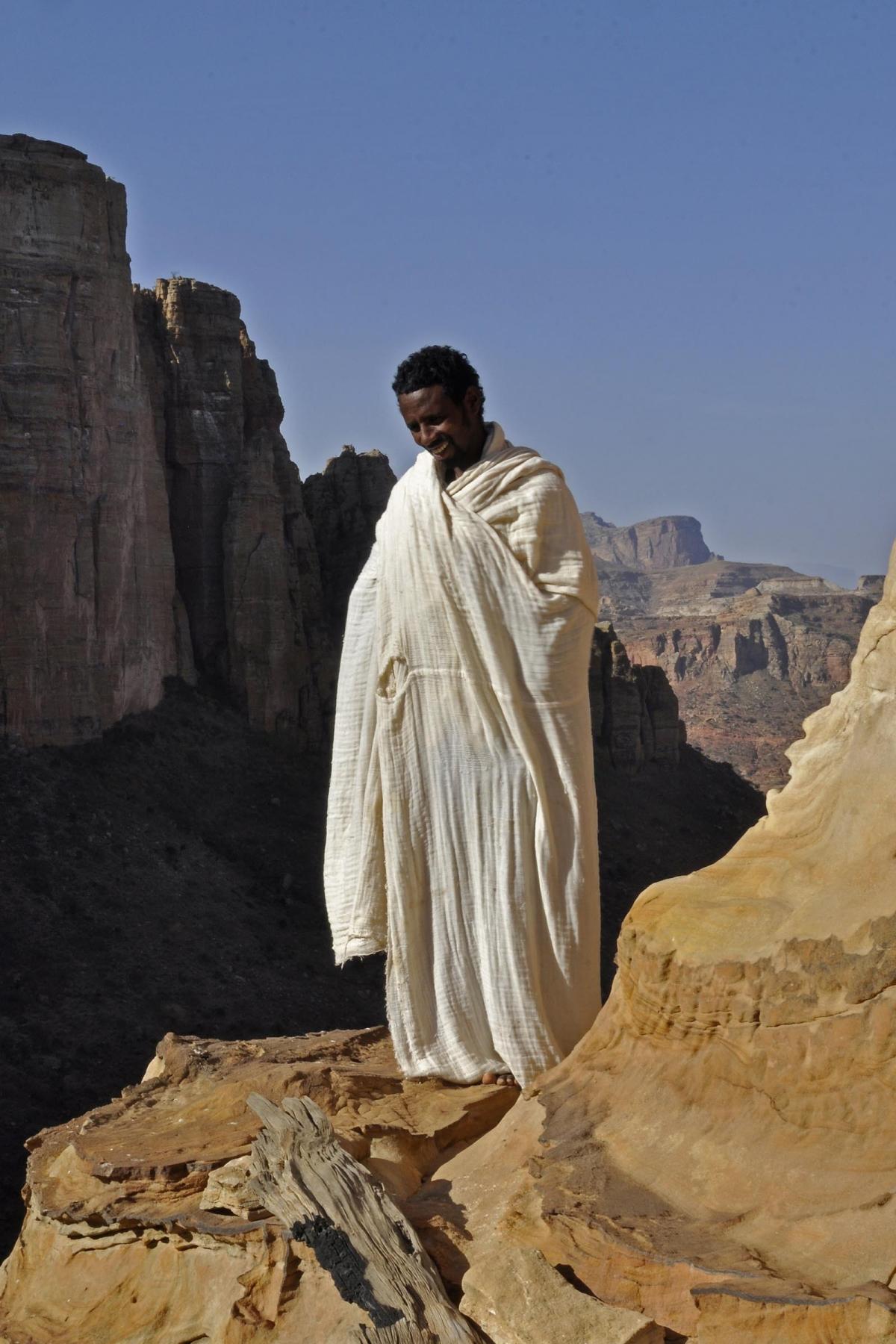

Ethiopians are passionately religious, and in the north they’re the most devout of all. Churches and mosques are at the centre of everything, and in some of the remotest places Orthodox monasteries have been cut out of solid rock. Many of them house priceless manuscripts.

I made a detour from the main road to a monastery that seemed purpose-built to keep visitors at bay. Debre Damo sits on the summit of a great table mountain. Legend has it that the original monks were whisked to the top by a serpent and an angel, but today it can only be reached by shimmying up the 50-foot cliff. A monk kindly passed me down a rope, but it was greasy and slippery from years of use, and if he hadn’t been yanking me from above I certainly wouldn’t have made it.

Then, like my predecessors 150 years ago, I pressed on south through the mountains. Some of these are home to the famous Gelada monkeys, but the paths are definitely made for visiting your neighbours, not for walking hundreds of miles. Many of the drops were lethal and I was lucky not to fall over them.

All along I was astonished by people’s kindness – pointing the way, practising their English, and inviting me into their houses for food and drink. I now had two companions – an Ethiopian friend called Gebru, and a donkey to carry my baggage. Despite their help the walk was one of the most difficult I’ve ever done.

So what are my memories of this five-month trip? Well my time in Eritrea – which has isolated itself from its neighbours and gets hardly any visitors – was a real privilege and eye-opener.

As for Ethiopians, they’re boisterous and charming and whatever the frustrations they never complain. In both countries, ox-ploughs and mud-and-thatch houses are the norm over wide areas, and these would have been familiar to the soldiers who marched through the same mountains all those years ago. But towns like Gonder are a joyous mix of ancient and new. If you haven’t been to this part of the Horn of Africa, you’re missing a treat.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here